This article is taken from PN Review 164, Volume 31 Number 6, July - August 2005.

Mythology without Myth: The Paintings of Timothy Hyman

'... je ne puis jamais considérer le choix du sujet comme indifférent... je crois que le sujet fait pour l'artiste une partie du génie.'1

What all Timothy Hyman's paintings seek to create is not so much myth, still less allegory, as a kind of personal iconography that will resonate beyond the literal premises of his subject-matter, a narrative that turns the anecdotal into the emblematic. Because he is a modern artist this iconography has to be invented and home-made rather than inherited. Its source is the imagination, not what Philip Larkin crudely called 'the myth kitty', and our response to it has to be imaginative, not just exegetical.

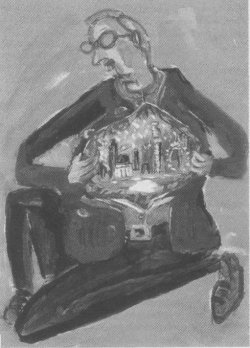

The notion of a subjective myth may seem contradictory - autobiography is not a communal form - but in a secular, post-classical culture there may be no other alternative to it. But if Hyman's art is personal, it is not self-centred. His aim is always to switch the self into some realm beyond it. He does this with a disarming directness, spurning the kind of sophistication that has become the bread sauce of British art. Hyman strikes no knowing poses. A painting like I Open My Heart to Reveal London Within may be violently self-revealing but it is not confessional: the emotion actually refers to something as complex and communal as London, the personal in the impersonal. Such violence is what one expects at the birth of a myth. What is unusual in this case is that the image also has an unsettling naïveté, wearing its heart on its sleeve. We would expect a painter celebrating London to be more hard-bitten and street-wise. In fact, the naïveté is Hyman's way of by-passing the predictable kind of urban decorum the subject seems to impose on him.

This is perhaps more a reflection of the painting's spirit than of its style but one of its effects is that Hyman's paintings seldom look composed in a studied way. At first sight, they seem sprawling and muddled, echoing an aspect of English art that goes back to Gillray and Hogarth. This impression is compounded by his fondness for vortexes and ellipses and his delight in wide panoramas. Often, the image is seen as if in a distorting convex lens. There may be drawing behind it (drawing matters deeply to him) but it is not a constructive, hierarchical kind of drawing. Each element in the image has an anarchistic equality with every other, the freedom of a world turned upside down. Thus, he finds an ideal subject in 'The London Eye' as it whirls round in a congeries of disparate impressions, with the artist clinging on. The topsy-turviness is the point. Another London painting, The Square in the Circle, also defies us to take a single view of the city. The square is Myddleton Square where the painter lives - we see him emerging from his front door - and the circle is a panorama of high-rise buildings, half of which seem to be upside down. London is a rag-bag, no one aspect of it takes precedence over any other. All that guides the questing artist is his dauntless faith in serendipity. What he values is not 'the classically beautiful river' but the chance to register 'a new configuration at least once a week'. To do this he has to 'internalise the locality of the city'. The result may be a kind of myth but not one that records any political or social map of London, as in a nineteenth-century novel. The experience is a visual one: London is what London looks like. This does not mean that its essence is just tall buildings and bridges and the like. It is also very much a London of Londoners, ordinary souls struggling along windy pavements or squashed in a shuddering London bus. Visually, the painter sets out to meet and bond with such people as they interact with their surroundings; what he does not do is to analyse them as a sociologist would. The eye offers more angles on them than that.

Hyman's art goes on from this into a kind of private symbolism but it is worth relating it first to the sort of abstract painting it seems to reject. Its deployment of colour and line, of expressive spatial distortion, has more in common with abstraction than meets the eye. Often, when we call a picture abstract we are simply using abstract terms to describe it. One sees this, for instance, in the way Bridget Riley talks about her art. She draws a much sharper distinction between modern art and the art of the past than Hyman would:

Figurative painting without the relevant context of religion or mythology won't do - it's no longer a language... I can see no real alternative to abstract painting... because the absence of a shared vocabulary is, by virtue of its absence, the only common basis that exists.2

Riley makes a virtue out of a lack though she does not deny the power of myth in a painter such as Titian (the Bacchus and Ariadne is one of her favourite pictures). For her, though, myth is no longer much more than a clutter of anecdote and decoration that distracts the artist from essentials:

... a kind of formal thinking is capable of providing an equivalent to that missing universal vehicle... formalism is not an empty thing but a potentially very powerful answer to this spiritual challenge of an unavailable truth.3

The abstract painter is not so much the schismatic of legend as someone who is obliged to pursue similar ends to the figurative artist by radically different means. There is, after all, a sense in which any visual artist, absorbed in line and colour, is an abstract artist. As Baudelaire, with the highly literary Delacroix in mind, puts it, 'Une figure bien dessinée vous pénètre d'un plaisir tout à fait étranger au sujet.'4 The image is in itself a kind of content. This does not mean that Baudelaire is reneging on his faith in the subject itself: he expects art to work in both ways.

One may not be convinced by Riley's polemics but it is hard not to admire the honesty with which she argues them. In the Mondrian show she selected for the Tate a few years ago she bravely - perhaps quixotically - included his one large, symbolic subject-picture, Evolution. Her point was to indicate the kind of picture a modern painter could no longer bring off. Mondrian's triptych of aspiring, ice-blue nudes is something of an embarrassment to his admirers, both futuristic yet oddly dated. It seems portentous but it is hard to say exactly what it portends, as if it hankered after some meaning that eluded it. The streamlined figures feel gratuitous and the whole atmospheric hinterland of myth that one expects to gather around such subject-matter seems to be short-circuited.

Mondrian never finished Evolution, nor did he ever try to repeat the experiment. The paintings he did immediately after it drew not on symbolism but on real Dutch landscapes. His cool blues show to more advantage in pictures such as The Blue Tree. For Riley, any consequent restriction in range has to be accepted by the modern artist as a fait accompli: 'a common social language does not lie within the scope of an individual and the lack of such a basis has to be accepted by Modern painting'.5 We see this embracing of limitation in Riley's own early work in the way she confined herself to black and white and, gradually, grey, as if she could only come at colour in her own time, shorn of its Titianesque associations. Her response to the unprecedented freedom of abstraction was to cultivate self-discipline. In this respect, Hyman is as different from Riley as he is from what Mondrian stands for. His paintings seek to include as much as possible, to accumulate subject-matter from the flotsam and jetsam of the mind. He admires artists such as Gillray and Ensor who have little time for symmetry and a strong taste for carnivalesque excess. Abstraction leaves out precisely what most interests him: atmosphere, tone, touch, the disarray of appearances. In other words, he is drawn by the very things that Mondrian was unable to include in Evolution. His colour and line are not self-contained entities but a function of the swarming subject-matter he wants to open his painting up to.

Each of Hyman's recent shows has centred on large auto-biographical pictures that seem more about raw emotion than balanced form.6 Cool cleverness and self-reflexive 'irony' are refreshingly absent. So too is the familiar claim to be 'art' - as if art were ever anything but the sum of the art that goes into it. As an historian, Hyman avoids slogans. His pictures are rooted in private feeling but they are neither portentous nor self-regarding. Indeed, the impression they make often seems disarmingly makeshift, their composition almost higgledy-piggledy. There seems to be no time to order the material in more than a provisional way. Any sense we have of the prestige of the large subject-picture is undercut by hints of the cartoon and the caricature. The result is urgent and yet oddly take-it-or-leave-it. This may feel like carelessness but it seems better to put it down to the artist's respect for the independence of his subject-matter, a refusal to doctor its meaning or coerce it formally. An image does not have to be a thing-in-itself.

It might, then, be tempting to think of Hyman's large pictures as narratives, even though the notion of narrative has often been an ominous one for English art. He was, after all, the curator of the great Stanley Spencer exhibition at Tate Britain in 2001. Yet it is more accurate to think of his pictures as searching for narrative rather than as over-arching narratives in themselves, fables that we can tap into to make sense of the whole. Even a picture that refers to a known narrative, such as the Dantesque In the Middle of the Way of our Life, only half corresponds to its source. In Hyman's wood, the painter's way is barred by a skeleton, not by the splendid allegorical beasts that confront Dante. Nor is the ingenuous painter remotely like the sternly impassive poet. He pops up constantly, often, in the medieval way, more than once in the same picture, and with never a thought for his own dignity. It is as if objective narrative has been taken over by its subjective content. (The method owes something to Kitaj.) It is in this context that one has to see those paintings that do seem to have a quasi-allegorical character. The Gandhian Ark, for instance, one of the most original, alludes to the myth without insisting on its universality. The inmates are too quirky for that: Gandhi's bald head looms out of the ark, a melancholy John Cowper Powys leans over the prow while the (diminutive) painter himself is bunched in the middle, overshadowed by his wife, all of them as much excluded as saved from the civilisation they sail away from.7 Such figures are not inaccessible but part of them remains private. If we wish to make the picture into a grand narrative (an ecological one, for instance) we have to supplement it from our own imagination. The painter can only take us to the water. The same thing goes for a very different picture such as Painting the Family, the large group portrait that was the highlight of Hyman's 2003 show at Austin Desmond. It too depends on a wry self-mockery. The grey, fumbling painter, all arms and legs, struggles to capture his family as they bear down on him. His late twin brother, aggressively highlighted, seems to crowd out his cowering sibling. We press forward from the painter's tentatively grasped brush only to find the picture's subject falling back onto us. This momentum and recession are constant. Despite the boldness of the painting's colour there is some-thing putative and half-complete about it. One thinks of it in the same breath both as a family portrait, as full of tension as of family feeling, and as a kind of spiritual geography. The artist seeks for himself in those closest to him but whether he finds himself through them is not so clear. If there is a narrative there it has not been spelled out.8

Not many painters who are this preoccupied with self avoid becoming self-important. The Cain-like figure of Byron, nursing his club-foot and baring his breast, dies hard. Self-portraits so often betray narcissism because their subjects like to see themselves as singled out by fate; hence all those consciously posed images of the young Courbet, basking in being himself. Not everyone is detached enough to paint himself as if he were painting a plant or an animal as Lucian Freud does. Hyman, however, is different from either Courbet or Freud: any warmth he shows to himself he leavens not with pitiless realism but with humour. He appears in his pictures as a gangling, pin-headed innocent, vulnerable but plucky, sallying forth into the battle of life, a holy fool like Perceval, naïf enough to confront the world and yet withstand the shock of it, Chaplinesque in his determination to keep going. This stance reflects not some theatrical attitude but a kind of raw curiosity in life. It is there, for example, when he steps back aghast from the skeleton in the Dantesque wood: it is horrific but it is also a new experience. The point of the narrative is not so much the self that serves as its medium as what that self enables us to see beyond it. For Hyman, to see himself in such a tongue-in-cheek way, uneasily dabbing at the canvas as if it would come down and bite him, is, in other words, a way of privileging his subject-matter over the subjectivity he brings to it. It is also a way of projecting a sense of wonder without recourse to heroic Blakean gestures. The hard-stressed artist of Painting the Family is his equivalent of Blake's Glad Day.

Not that this difference should deflect attention from Hyman's debt to Blake, even allowing for the contrast between his salutary untidiness and Blake's 'wiry, bounding line'. There is a sense in which they share a common starting point. As Hyman made clear in an important early essay,9 Blake found himself obliged to fashion (or fabricate) an iconography of his own for want of any more common one that he could draw on. In a sense, it was the poet who made the painter possible: Los, Urizen and the rest, the protagonists of the Prophetic Books, have no real antecedents. Only Blake could transform them from mere names into powerful images. As T.S. Eliot said:

What his genius required, and what it sadly lacked, was a framework of accepted and traditional ideas which would have prevented him from indulging in a philosophy of his own, and concentrated his attention upon the problems of the poet.

This lack of a 'framework' deprives him of the 'classic' authority of a Dante:

The fault is not perhaps with Blake himself, but with the environment which failed to provide what such a poet needed; and perhaps the circumstances compelled him to fabricate, perhaps the poet required the philosopher and mythologist...10

Hyman clearly begins from a similar point in a painting such as The Gandhian Ark, though his imagery is less self-generated. He still runs the risk of being accused of creating something than is more like a willed concoction than a myth. To Eliot, this lack of an available mythology was a severe disadvantage to any artist and Hyman may also have felt it as such. Reading between the lines of his perceptive study of Sienese art,11 it is hard not to suppose that he must some-times have envied Duccio and his followers their common store of symbolic motifs such as that of the Maesta. In a secular age, such imagery has to be invented from scratch. Where Hyman remains Blakean at such a juncture is in his determination to maintain his links with older art and not, like Mondrian, to rule its symbolism out of the equation.

This is not simply another way of contrasting abstraction with figuration.12 In a fuller account of Hyman's art one would want to say much more about the vibrancy of his colour and, in so doing, one might elicit more links between it and Bridget Riley's colour than its subject-matter suggests. But the real distinction to stress is between an art that is finished and perfected and an art, like Hyman's, that remains tentative, 'evermore about to be' as Wordsworth put it. Riley crystallises her vision in a decisive form; Hyman wields his brush like an instrument of speculation. His pictures carry his mind along with them, hers feel directed and marshalled by her mind. It is surely because she has her pictures so much under control that she can afford to have them coloured for her by assistants. In dispensing with myth, it turns out that she also dispenses with touch, with the brush-stroke itself. The hard-edged clarity of her line and the mechanical opulence of her colour have no truck with atmospherics. Nothing could be further away from an old master like El Greco, putting the last touch to a sitter's eyes, as if a single brush-stroke bore within it the whole world of the spirit. Yet however we view this difference, it is clearly too far-reaching to be set down just as a matter of 'finish' or 'technique'.

What is at issue, rather, is not so much the art of painting itself as how free it can be in drawing on the imaginative experiences that feed it, on what might be called its poetry. I make no excuses for using this elusive word since it should be clear that much of what I have been saying about the roots of painting also applies to poetry. Our poets are often as distant from religious and classical myth as our painters are. They feel more at home in the company of Philip Larkin than of John Milton. Yet this does not necessarily mean that their work is destined to be relativist and secular, any more than that the painters are forced to choose for or against abstraction. The effort to create something new out of the traditions of the past still goes on. Poets such as Ted Hughes will still try to recuperate ancient mythologies, whether the bright sparks of the poetry circuit think it feasible or not. That is something that only the poets and painters can decide, in their practice, but the critic is faced with choices too. Simply to say that what a Hughes attempts is impossible is to imply that modern poetry and painting are obliged to settle for less in what they attempt than the poets and painters of the past - Blake as well as Titian - would have settled for.

One of the lessons of Mondrian's Evolution is that modernism can sometimes be defeatist, a kind of capitulation. This is why we need to take seriously those artists who seek to go beyond it. There is no need to locate the modern in a sense of impasse. Riley's kind of art is not always a dead end. Sometimes abstraction lets back into the picture some of the emotion it had apparently excluded from it. Thus, certain of her later paintings embody her sensuous experience of visiting Egypt whilst still remaining as abstract as her earlier paintings are. This paradox was already evident to one of her own heroes, Paul Klee:

If the artist is fortunate, these natural forms may fit into a slight gap in the formal composition, as though they had always belonged there.

The argument is therefore concerned less with the question of the existence of an object, than with its appearance at any given moment - with its nature.13

Nature itself is a construction, something realised through art and not merely its raw material. Klee's 'slight gap' offers a home to both abstract and figurative impulses. One might cite, for comparison, the art of Ivon Hitchens, a painter whose work is poised gingerly between landscape and abstraction. Hitchens's paintings can be read as pastoral but they can equally be seen as free swathes of bright colour like huge brush-strokes that form their own chromatic world. One way of seeing them need not preclude the other. There is no point in being too prescriptive about what goes on in Klee's 'slight gap'. Nor should we simply label Riley as a geometer or Hyman as an illustrator and leave it at that. To explore the 'gap' fully an artist is more likely to need to approach it in more than one single way.

Notes

- Baudelaire, Curiosités Esthétiques (Garnier, 1962), p.381.

- Bridget Riley: Dialogues on Art, ed. Robert Kudielka (Thames and Hudson, 1995), p.29.

- Ibid., p.29.

- Curiosités Esthétiques, p.433.

- Mondrian: Nature to Abstraction (Tate Gallery, 1997), p.11.

- Hyman had shows at Austin Desmond Fine Art, London in 2000 and 2003. In January 2005 some of his London paintings were shown in Taking on London at the Museum of London; other paintings (including The Gandhian Ark) were shown in 2005 at Flowers East, London.

- Hyman's devotion to John Cowper Powys has been a refrain throughout his work. At the risk of simplifying it, one might point out how much he owes to Powys's unselfconscious fluidity of self-revelation, particularly in his extraordinary Autobiography (1934).

- Compare the figure of Goya in the same left-hand foreground of his great group portrait of The Family of the Infante Don Luis in Parma, a painting on loan to the National Gallery at the time Hyman's painting was being completed. (This is by no means the only time one finds an echo of Goya in his work.)

- 'A Blake for Today', Artscribe, No 11 (1978), pp.22-7.

- Selected Essays (Faber, 1951), p.322.

- Sienese Painting: The Art of a City-Republic 1278-1477 (Thames and Hudson, 2003).

- If one compared Hyman with more organic abstract painters - Arshile Gorky, say, or Ivon Hitchens - this difference might be less obvious. The issue goes deeper than style. But in talking about the poetry that there is in Riley's best work one is not talking about just one kind of poetry. It would be misleading to think of her simply as a classicist or formalist - she admires Delacroix as much as Poussin, even if the Delacroix she admires is Delacroix the colourist, his colour split off from his iconography. She has no taste for 'literary' painting - witness her rooted dislike of Caspar David Friedrich. In other words, for her only some parts of the past deserve to be transmitted into the present. As with the Evolution panel, the sticking-point is subject-matter. Far from finding an invitation in it as Hyman does, she wants it to be filtered and screened for impurities.

- Paul Klee on Modern Art, introduced by Herbert Read (Faber, 1966), p.33.

This article is taken from PN Review 164, Volume 31 Number 6, July - August 2005.