This article is taken from PN Review 276, Volume 50 Number 4, March - April 2024.

Pictures from a Library

Alarming Invisibility in a Byron Facsimile

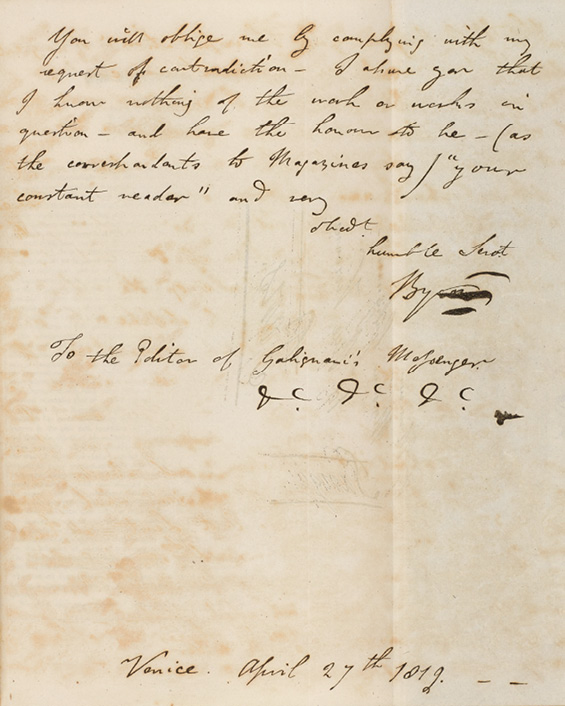

A facsimile of a letter from Byron enclosed in Galignani’s edition of The Works of Lord Byron, 1827. (© University of Manchester 2023)

Claimed as the work of Byron, the publication of the ‘The Vampyre’ in Henry Colburn’s magazine New Monthly caused a sensation. Deemed to be an accurate self-portrait of the poet, it ‘profoundly shocked and titillated’ contemporary readers in equal measure (Franklin Charles Bishop). After much deliberate twisting of the truth, John Polidori was named as the text’s true author, but not before Colburn had entered its title and Byronic attribution as a separate book at Stationers’ Hall, thereby securing its copyright. His bloodsucking catchpenny trick exhausted ‘five London editions before the year’s end’ at the rate of 4s 5d apiece (Nick Groom). Exposing anxieties over authorial authenticity in a period that prized originality as literary genius, this grubby episode demonstrates how booksellers benefitted from the commodification of Byron’s assumed or imagined persona. Unhappily for His Lordship, the perfidy of publishers took various forms. Their treatment of Byron as a means of maximizing profits meant that his work was often subject to unchecked piracy at home and abroad (Jason Isaac Kolkey). France became the centre for the unauthorised reproduction of English works, a practice that was led by the Anglophile Italian booksellers Galignani. Byron’s poems, in their various iterations, in turn became the ‘driving force… and backbone’ of their list.

Galignani’s edition of The Works of Lord Byron was published in 1827 and contains all of the poet’s poems, augmented with paratextual elements including an account of his life, a portrait of his likeness and (in a pre-photographic era) a lithographic facsimile of the handwritten letter he sent to Galignani denying authorship of ‘The Vampyre’. Seemingly a ‘perfect duplication of the original’ (Barry Gaines), it ‘has fooled book collectors and autograph dealers ever since’ (Leslie Merchard). So, through the tangible form of this book readers are invited to meet not only the corpus of the work, but also the authentic person of the poet, certified by the facsimile of the handwritten autographed letter (shown here). For nothing ‘bears so exclusively the stamp of an individual as their handwriting’ (Johann Kaspar Lavater), which in the case of an author has the ‘capacity to disclose their intrinsic personality’ (Tom Young).

Yet, in comparing the facsimile with Byron’s actual letter (now held in private hands), we find it not to be a perfect duplication of its source, for one of its sentences is missing and the substance of its meaning is changed through ‘skills alarming in their invisibility’ that leave no trace. And while this tampering with the meaning of this text may seem slight, its impact on its integrity as a document of record is substantial, for archives should be ‘fortresses of the first hand’ (Schwartz). Here, ironically, the authentic version hides in private hands while its manipulated surrogates abound in public collections, ‘circulating as true originals to confuse the historical record’ (Schwartz).

This article is taken from PN Review 276, Volume 50 Number 4, March - April 2024.