This article is taken from PN Review 275, Volume 50 Number 3, January - February 2024.

Pictures from a LibraryA Handkerchief and Its Genealogies

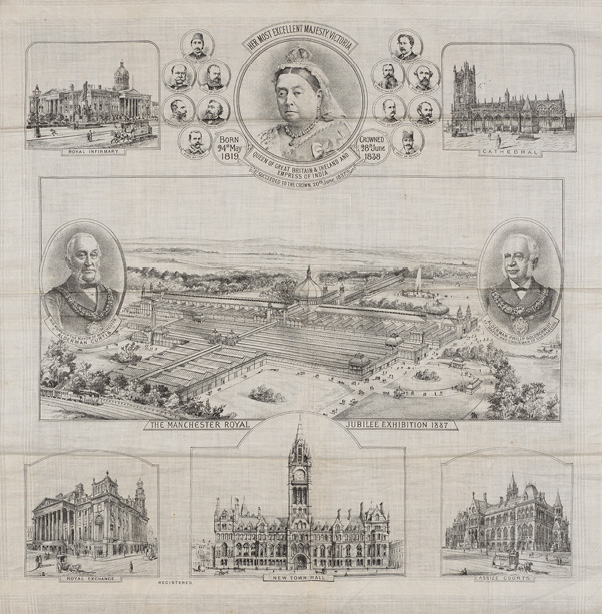

The Manchester Jubilee Exhibitions Commemorative Handkerchief, 1887

Claimed as an invention of Richard II, the handkerchief is said by some to have its origins in the opulence of his court. In an age when all tended to wipe their snot, sweat and tears on sleeves, incredulous eyewitnesses observed Richard swanning around with little pieces of fine linen fashioned by his tailor Walter Rauf to use for the outlandish purpose of blowing and wiping his nose. Patron of poets, connoisseur of art and fashionista,

Richard was also ‘almost irritatingly’ fastidious in his habits, preferring ‘beauty and refinement to war’ (Michael Senior). Much to the disgust of his magnates, he failed in his first kingly function as a warrior, for his ‘true emblem was the handkerchief… not the sword which he never successfully employed’ (Bertie Wilkinson). Finding his patronage of the arts and the hanky ‘extravagant and effeminate’ (A.R. Myers), they sought to curb his power. In response, Richard self-consciously deployed the handkerchief as a weapon in a ‘politics of courtly style’ that reinforced his ‘autocratic rule’ (Patricia Eberle) as his supporters sported it as a mark of their allegiance. And so an object as seemingly mundane as a handkerchief is ‘not just a docile thing’ but a ‘sign or showing… invested with powers, associations, and significations… that apprehend us’ (Steven Connor). The inquisitive amongst us will therefore wonder what adumbrations skulk within the warp and weft of the object shown here.

Made in Manchester from the actual cotton of Cottonopolis, this handkerchief ostensibly commemorates Queen Victoria’s Golden Jubilee in 1887. Emblazoned with her portrait, and those of her ilk, it pays homage to her power and privilege in echo of her ‘forebear’ Richard. Yet, the other images printed onto its surface show a series of magnificent Mancunian edifices including the town hall, cathedral, infirmary, and exchange, which tell some of the stories of a city swaggering with self-admiration. Exemplified in the iconography of a handkerchief, Shock City’s merchant princes seek to present the modern metropolis as a ‘symbol of progress and a cradle of wealth [where] new formative social values [within the] public sphere take prominence’ (Linda Mulcahy).

Yet in addition to the civic pride made manifest within this hanky I too am implicated, for it quivers with the incendiary power of a personal secret hidden for generations in, but from, my own family. Branded on the lower right corner is a miniature version of the Courts of the Assize, the site where, it has recently been revealed, my great-great-grandfather stood trial for the murder of his son. Convicted of manslaughter, he was sentenced to a life of penal servitude, never again to be reunited with his wife, to the affliction of both. If, as scientists say, a human being may be identified from the DNA deposited on a handkerchief from their tears, what other ‘pocket homilies’ might it tell me of ‘the love, time, hope, error, striving and death’ (Connor) of these my near ancestors?

This article is taken from PN Review 275, Volume 50 Number 3, January - February 2024.