This report is taken from PN Review 273, Volume 50 Number 1, September - October 2023.

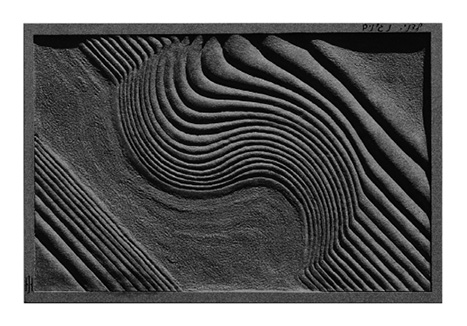

A Stone for Daniel Pearl

Credit: © Tom Bonner

The inauguration of the Rabin Peace Memorial at UCLA Hillel in Los Angeles in 2004 was a solemn celebration and the path to the unveiling long and difficult. A few years earlier, living in Jerusalem, I had been contacted with regard to a commission for a sculpture to honour Yitzhak Rabin, the Prime Minister of Israel, assassinated in 1995, barely eight years before. Few murders have had such far-reaching repercussions. I wrote at the time: ‘Unlike war memorials, the Rabin Peace Memorial does not recall historical events. It honours the ideal of reciprocity and justice in our relations with others. The rendering of the figures in sunken relief is an acknowledgement of the second commandment. The events in the life of Yitzhak Rabin which inspired this work remind us of how difficult it can be to distinguish illusion from reality.’

After the unveiling, a small elderly couple waited patiently as I spoke with the other guests. I had never seen them before and when they finally approached it felt as if something unexpected was coming. As they glanced up at the dark fossil-like figures that hung over the entrance to the building, they expressed their hope that I might be able to help them. ‘My name is Judea Pearl and this is my wife Ruth – we are the parents of Daniel Pearl... perhaps you have heard of us? Have you ever made anything for a cemetery?’

I have no words to describe what my feelings were as I absorbed their presence. Their son, a young American journalist, had been kidnapped and decapitated in Pakistan. Al-Qaeda then broadcast a gruesome video throughout the world as anti-Zionist and anti-American propaganda. The media had been filled with shock, dismay and endless speculation. The French author Bernard-Henri Levy had published the book Who Killed Daniel Pearl? and Mariane Pearl, Daniel Pearl’s widow, had published A Mighty Heart. I had read both.

Their request, on the surface, seemed simple: that I create something to mark the resting place of Daniel Pearl. I learned that he had been buried over two years before, at the Mount Sinai Cemetery, ten miles away. Within a few days of our meeting, Judea Pearl invited me and my wife to join him there. Under an intense blue sky, we found the Mount Sinai Cemetery reminiscent of parts of Israel, simple and austere, although the carefully manicured lawns reminded us this was indeed southern California. The graves were all marked by bronze or stone plaques flat on the ground. I was struck by the innocence of the place – no trace of history or violence, no broken stones, nothing like the old Jewish cemeteries of Europe. There were few tangible forms of remembrance, apart from inscriptions. Given the circumstances the cemetery director had granted the Pearl family special permission to honour their son on a stone wall adjacent to the plot where he was buried. As we approached the site, we noticed a small temporary label stuck on the ground. I felt an overwhelming emptiness and solitude, and understood the reason I had been brought here.

After our visit we returned to the Pearls’ home and over tea, they began to share everything they could about their son. Family photos, videos, published articles, memories of those to whom he had been dear – everything to bring me close to Danny, as they always called him. He was a fine journalist, unafraid to explore a conflicted world, and a talented violinist. He was on the cusp of a new life as a father. They conveyed all this with love and even humour. Their sorrow was bitter and palpable, but never on display.

The Pearls had poured their energies into the Daniel Pearl Foundation, trying by every means to honour their son’s memory through the things he valued. Thus an annual world-wide music festival was launched, and a programme to bring journalists from developing countries for apprenticeships in America. Judea Pearl engaged in public, bridge-building dialogues with Akbar Ahmed, a leading authority on contemporary Islam. The Pearls published two books with titles that spoke for themselves – At Home In the World, a collection of Daniel’s Wall Street Journal articles and another, I Am Jewish – Daniel Pearl’s last words – a collection of short essays from a large range of public figures. Every year renowned journalists and public intellectuals would give lectures in his honour at UCLA and Stanford.

Any sculpture I might imagine would have to be about three by two feet and would be placed on the wall perpendicular to the grave. I was told it could be made of granite or marble, and I knew from the start that I would choose granite. Another stone would lie flat on the ground and would carry text. I was honoured by their request, but within I felt troubled – I had no idea what I could possibly do to relieve the atmosphere of profound sadness that enveloped me as I stood there by that empty place knowing what we all knew. It felt like there was nothing to say, or do, except to bow one’s head.

They always referred to him as Danny and it was contagious. I began to feel I knew him, and I would find myself wandering cemeteries looking towards the sky seeking guidance from him. I wanted to find a way to eclipse the morbidity, to shift the experience of this place, to somehow move the mind to another plane. At one point I was at a loss and suggested to Judea and Ruth that we ought to create a memorial at another location. But they were adamant that something was needed here, something beyond words. At one point they suggested that I include a violin and a pen on the wall stone. Nothing so literal, I told them.

In the end the solution came by looking skyward. Dramatic new images of the planet Saturn had recently been published and they suggested vibrations in cosmic space. I began to conceive of a pattern of resonance. The form would evoke music, but it would also embody shock, conveying a sense in abstract terms, of enduring memory and meaning. I produced dozens of patterns, shaping the waves according to some invisible harmony. When I showed them my final rendering there was no doubt I had found it.

Along with a traditional Hebrew text, the ground stone carries the following lines composed by Judea:

Journalist – Musician – Humanist

Lost his life in the pursuit of truth.

In one of the stars

He is still living,

In one of them

He is still laughing:

Perhaps in foreign places

He is still lighting the path of our world.

Originally I had not imagined an inscription on the wall relief. However we live at a time when even a cemetery can feel ephemeral. It was important that the stone always recall Danny, wherever in the course of time it might be found. His parents asked to have inscribed, in Hebrew, Nigunnim for Danny – Melodies for Danny.

This report is taken from PN Review 273, Volume 50 Number 1, September - October 2023.