This article is taken from PN Review 267, Volume 49 Number 1, September - October 2022.

Pictures from a Library

Reading in Wartime: Edmund Blunden & John Clare’s Village Minstrel (1821)

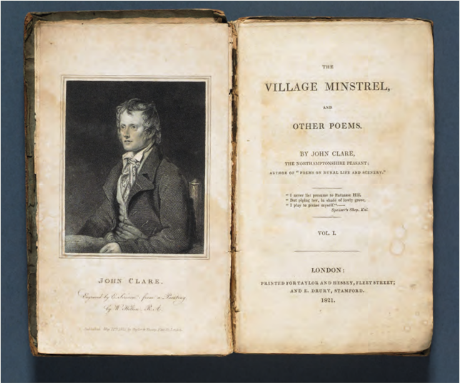

Title page of John Clare’s The Village Minstrel and other poems, with a portrait of poet, 1821 (R200210)

(© The University of Manchester, 2022)

When Herbert Read found he needed a book to carry around with him, that would ‘suit the various moods and circumstances of [his] unsettled existence’ as a soldier on active service in the First World War, he was not alone. Books became a ‘central component in aiding morale and alleviating boredom amongst the troops’ (Marcella Sutcliffe), and by the end of March 1919 some sixteen million had been sent from Britain to trenches, prison camps and hospitals. Detective stories were ‘shouted for’ (Red Cross Library) and favourite authors included Nat Gould, Kipling, and Dumas alongside ‘all sorts of penny novelettes’. In addition to sensational fiction, ‘poetry was in demand’ (Theodore Koch). Soldiers marched up the line with poems in their pockets and discussed in dugouts their power to ‘console, teach, amuse, enlighten, [and] disconcert’ (Belinda Jack).

Defying the idea that reading ‘takes no measures against the erosion of time’ (Michel de Certeau), they even left behind traces of their bookish experiences in written accounts and annotations in the books themselves. While these records and ‘marks of use’ can provide clues that bring us face to face with individual readers, ‘the voice of books informs not all alike’ (Thomas à Kempis) and sometimes evidence conflicts to reveal previously hidden histories.

Take, for example, the story Edmund Blunden tells about his copy of ‘John Clare’. Commissioned as a second lieutenant in the Royal Sussex regiment, Blunden saw continuous action on the frontline from 1916 to 1918. Despite surviving ‘without a scratch’, his mind was ‘indelibly affected by the death and destruction he witnessed’ (Bernard Bergonzi). Throughout, he is said to have kept a collection of John Clare’s poetry, edited by Arthur Symonds, as his constant companion, deemed crucial to his ‘coming through’ (Ronald Blythe). That is, until a fellow officer, Xavier Kapp, took it from him. ‘He has the book yet for all I know’ complained an annoyed Blunden in his memoir Undertones of War in 1928.

The loss of such a book would have been a blow rather than an irritation but for the fact we know that Blunden had other ‘Clares’ at the front that go unmentioned in his memoir. The edition held in the Rylands (shown here) is probably the most precious. This first edition of Clare’s Village Minstrel from 1821 lived in the same world as its author yet its curative force consoled its owner a century later. It carries an inscription in Blunden’s hand that reads: ‘Necnon poeta infelix. This copy I had in Flanders: hence the view intended above, E.B. 1923’. A prized but humble object, it reminds us that books are not ‘dead things but do contain a potency of life… they preserve… the purest efficacy… of that living intellect that bred them’ (Milton) which sustain those who read and live by them, especially in the ‘strange hells within the minds war made’ (Ivor Gurney) and continues to make.

This article is taken from PN Review 267, Volume 49 Number 1, September - October 2022.