This article is taken from PN Review 263, Volume 48 Number 3, January - February 2022.

Pictures from a Library

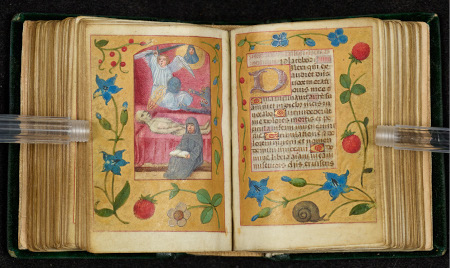

Pictures from the Rylands Library Mary Queen of Scots and her Book of Hours

This Book of Hours, seven centimetres long and five centimetres wide, dates from the fifteenth century. One of a number once owned by Mary Stuart, Queen of Scotland, it carries annotation in her own hand and provides ‘a deliberate record of her presence’ (Emily Wingfield) during the period of her long imprisonment in England prior to her death in 1587.

Although such books were used for private prayer and public worship across Christendom throughout the medieval and early modern periods they came to be associated

with Catholicism in Elizabethan England (Eamon Duffy). Like all Books of Hours it contains texts in honour of the Virgin, suffrages for the saints, dirges for the dead, psalms, and prayers for recitation at the eight monastic divisions (or hours) of the day. Adorned with jewel-like pigments and precious metals, its opulent religious images provide a devotional focus in their own right (Duffy). The image here, for example, from the Office of the Dead, invites the reader to contemplate their own mortality and to prepare for the life beyond. It shows a person, naked in their innocence and shriven of their sins, at the hour of their death. Their airy-thin, golden soul floats heavenward towards God, wafted like a feather on the breath of the friar’s prayers. Protected by an archangel’s sword, ready to resist the snatches of a lurking devil, the image exemplifies the art of dying well and provides a paradigm to emulate. All in seeming contrast with the end met by Mary, whose brutal execution and violent death appear to presage perdition.

Yet, might this little book provide Mary with the material means to achieve an afterlife amongst the blessed? Squeezed into scraps of space left by a scribe, her annotations call to God, her only judge, to hear her complaints and confound her enemies in echo of the Penitential Psalms. Her words acquire ‘a permanence both on the page and in the mind of memory’ (Wingfield) that gives voice to her authority and her ‘leadership... within dynastic and religious struggles’ (Rosalind Smith). And so she signals to her followers an aspiration to perfect a Catholic martyrdom with its promise of a State of Grace. Meanwhile, the Book of Hours, and the devotional regimes it implied, was increasingly deemed to be deviant. Seen in general as a ‘badge of non-compliance with the Reformation’ (Duffy), the particular example shown here became ever more hallowed.

Office of the Dead, Rylands Latin Manuscript 21, folio 147

(© The University of Manchester, 2022

(© The University of Manchester, 2022

This article is taken from PN Review 263, Volume 48 Number 3, January - February 2022.