This article is taken from PN Review 263, Volume 48 Number 3, January - February 2022.

Without Irony

About a year ago Adam Zagajewski wrote to me, and now his words echo as only last words can.

Dear Jonathan,

Today I’m crying for Wojtek Pszoniak who just died. As you know, when you lose a friend there’s an avalanche of things that come to your mind.

I knew Wojtek for 70 years, he was like a brother for me.

I’ve read your essay on Milosz, I like it very much, you’ve found a way

to capture his essence not only in clay but also in words.

It’s a pity that we’ve lost contact years ago.

Let’s hope that--at least--we can be in touch through words. I

remember many beautiful moments in your study, with leafless trees

outside

or spring trees.

Love to all of your family,

Adam

Last March I received the news that Adam was very ill. Initially there were some grounds for hope, but within barely a few weeks it was over. Suddenly it was I, struggling to restore coherence to my own recollections as he gazed from a pedestal a few meters away. “Leafless trees outside / or spring trees” - this familiar hesitation and this nod to time - Adam’s voice.

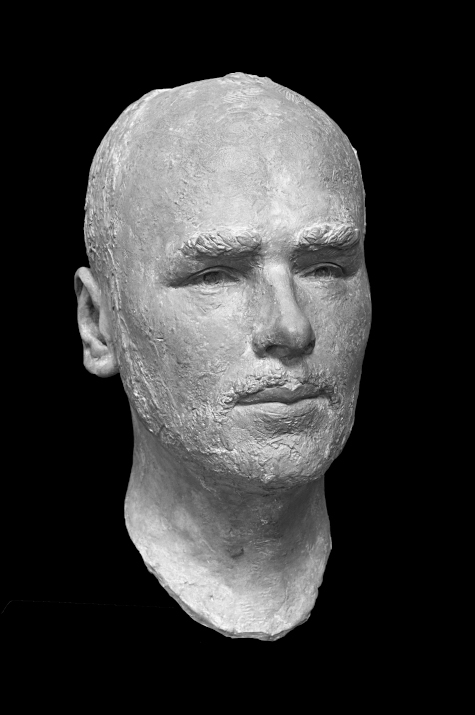

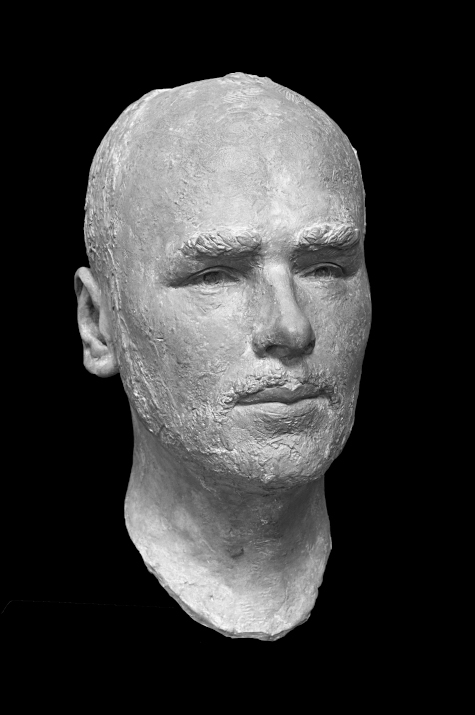

I have become familiar with this feeling of irrevocable void, but nothing can compress the time it takes to absorb it. My first reflex was to go to the sculpture. When I looked into his eyes, they looked beyond me – or within himself - I couldn’t tell. I touched his cheeks, and imagined the air on his skin. I noticed his unusual ears. His tilted, slightly pursed mouth still amused me, and his large baldpate somehow did not age him. From today’s perspective he looked young. I could feel irony in the slant of his mouth and the corners where the lips fold inward, and even a hint of humour, but not enough to undermine his sincerity and serenity. I had made him slightly larger than life, perhaps to compensate for his shyness; unconsciously, I think, so he could hold his own next to my Milosz. I imagined the conversation we might have had, decades after having made this. “We always seek what is gone for good.” (Another Beauty)

We met toward the end of the eighties, less than ten years after he had arrived in Paris, and a few years after I had arrived from California. The collapse of the Soviet empire coincided with this period and several of our mutual friends came from Eastern Europe. To a degree that is difficult to imagine today, the times were optimistic. I was touched and amused when he described himself not as a political, but as an erotic, exile who had fled to Paris in pursuit of the woman he loved.

He lived with Maja in a comfortable flat on the western outskirts of the city. It was simple and tasteful, enough for the two of them as well as Maja’s daughter, but no more than that. Six for dinner was about the limit. There was a wall of books, and music, and photos, which spoke for themselves. Adam with Brodsky, Walcott, Strand, and of course Milosz. The contrast with Milosz struck me at the time, not only the difference in age, but also a difference in substance. Ann Kjellberg captured it vividly. "He had this eyebrow-cocked devilishness and puckish curiosity that danced a bit above their sometimes ponderous self-understandings. Shyness was perhaps a feature." (On Adam Zagajewski – Bookpost, 22 3 2021). Adam was emerging from the shadow of his elders, but, more critically, he was confronted with a different challenge. At a time of intense political change he resisted his Polish contemporaries who believed a writer with his gifts ought to put them in the service of his country, as he had already done very successfully while still in his twenties.

I am reminded of what I saw and felt when I made the sculpture. He looked shy, yet warm, quiet, solitary and contained, watchful, extremely sensitive; a certain stillness. Yet there was also a current of inner motion, as if I could feel his mind at work, or more precisely, his way of sensing the world. This became a conscious theme for the portrait – a state of receptivity and preparedness, even his skin needed to feel like an organ of the senses. Within his way of being I sensed a quiet, determined strength. It took me some time to grasp that this demeanor was a reflection of his conscious urge "to dissent from dissidents". He held true to his contemplative gaze and to an unabashed search for beauty; he could write of the ecstatic and he believed in the soul – this was the form of his resistance, more radical than it might appear. A dissident in the regime of post-modern decline, he wondered how the clay could take that on. And I thought to myself, only clay could take that on.

Adam’s relationship to those around him was complex. In a poem entitled Self-portrait he told us:

[…]

Sometimes in museums the paintings speak to me and irony suddenly vanishes.

I love gazing at my wife’s face.

Every Sunday I call my father.

Every other week I meet with friends,

thus proving my fidelity…

(from ‘Mysticism for Beginners’ 1997)

This felt like a confession and it surprised me, because Adam showed his fidelity in countless ways. Early on we had shared our appreciation for a proverb that we only knew in English, by Malebranche, a French eighteenth-century religious philosopher: "Attentiveness is the natural prayer of the soul." One day, out of the blue, a fax arrived from Houston with an affectionate note addressed to each of the three of us in my young family, along with a copy of the text in the French original. As I prepared to write this essay I discovered the fax folded into my copy of Mysticism for Beginners. Adam was aware that for us these were not idle words. Once Mariana bumped into him at a railway station, as she was accompanying our son to a school for children with special needs. Adam called out to Anton, whom he hardly knew, and embraced him with open arms, as if nothing could ever stand between them.

Adam Zagajewski, polychromed plaster (© Hirschfeld, 1990)

One day Adam asked if we could use my studio as the setting for a documentary about him to be filmed for German television. We had spent many hours together in this luminous space, working against the background chatter of chirping birds that he loved and recognized. There is a sequence in which he meanders through the atelier and settles on the small head of a young boy, for which he felt a particular affection. As I watch this video today I am reminded of his affirmation, with which he concluded his Neustadt lecture in 2004, that "innocence is perhaps the most daring thing in the entire world." The camera panned across the collection of portrait heads. Adam was among them. On the shelf they were all equals, memorable for the kind of human beings they were.

Adam’s thoughts could take you from Las Meninas in the Prado to Balthus, from Bach to Mahler, sharing his enthusiasms. Yet he was not a snob: "French intellectuals love to look down their noses at Americans and their boorishness, their lack of taste. France …. frequently fails to understand American enthusiasm. An example: once I was standing before one of the Vermeers in Washington’s National Gallery. An American, about forty years old, stood beside me. At one point he turned to me and said (his voice trembled with joy), ‘I’ve been looking at reproductions of this painting since I was twenty, and today I am seeing with my own eyes for the first time. I’m sorry to bother you, but I had to tell someone.’ I can take such lack of culture any day." (Another Beauty)

Once Adam began a university talk with a quotation affirming "It is certainly not the mission of the mind to defend the world dominance of money. Hardly any system was so detrimental to the basic human values as that of capitalism." After describing the police state in which he grew up, he showed his hand. "I hope I have sketched the epistemological situation of someone living in a Communist country clearly enough. And even if this someone – that is, me – would be inclined to adopt a rather aristocratic perspective and to pay homage to artistic and religious imagination rather than to the rules of the free market, he would find it difficult to forget and to renounce his totalitarian experience. Therefore I have no intention of repudiating my old affinity to the human reality as it was described by Balzac. I think I can reveal now that I do not agree with the thesis expressed by Erich Kahler. Yes, it is the mission of the human mind to defend money and the market economy, though it should not be its exclusive and uncritical mission." Adam was his own man.

Expatriates from Eastern Europe were clearly different from their counterparts from North America. Similar things may have enchanted us - the miracle of post-war Western Europe was something to behold - but behind each of us were continents of unshared experience. « The West Berlin of the early eighties struck me as a peculiar synthesis of the Old Prussian capital and a frivolous city fascinated by Manhattan and the avant-garde (sometimes I suspected that the local intellectuals and artists treated the wall as yet another invention of Marcel Duchamp)”. (A Defence of Ardour)

When Adam laughed it was as if he was bubbling up from within, literally tickled by his own thoughts. "I don’t see any fundamental contradiction between humour and mystical experience; both serve to wrench us out of our immediate, given reality." (A Defence of Ardour) I recall a dinner when my wife was bursting with our unborn son. A home video shows Adam playfully tasting the stuffed cabbage and entertaining us with a humorous account of the American feminists that he had only recently discovered in Houston, Texas. As I remember his laughter, I struggle to come to terms with the photos of a much older gentleman that illustrate the eulogies in his memory. Time itself had sculpted my friend. He had matured, and handsomely, but I was grateful to have caught him at a stage when he was still becoming.

Sometimes I felt that Adam and I were like animals from different species that happened to meet by the same river, propelled by a similar thirst. Neither of us had come to Paris by accident but we were bound there, more deeply by love for a person than by love for the place. This made for a mostly unspoken understanding. During one long walk through the city I recall discussing a theme that affected each of us in different ways, the impossibility of witnessing an artist at work. In a conversation with Edward Hirsch he comments on his friendship with Zbigniew Herbert; "…but we never actually see the person in poetic action, there is this hidden life of the poet, there is something so shameful, or at least very discrete in the poet who is in the act of writing, or inspiration… you never see it. So these friendships are not touching upon the deeper layer…", (https://podcast.lannan.org/2009/07/09/adam-zagajewski-with-edward-hirsch/) In a poem entitled “Poets Photographed”, Adam observed that photographs never show the poets "when they truly see”, “never in darkness, never in silence”, “at night, in uncertainty, when they hesitate, when joy, like phosphorus, clings to matches."

The human face is our first landscape. It offers wholeness and unity, even as the idea of the singular human personality has been slowly disintegrating for more than a century. Inner awareness and inner gaze matter as much as the way a person attends to the outside world. The common denominator is consciousness. Often I am trying to reveal something in my portraits that I cannot so much see, as feel. We tend to put the emphasis on vision, as if the key to the art of portraiture is the accuracy of the record. Technique is imitable, but not the synthesis. True essence lies in empathy, the only channel that can reveal the invisible.

For many in Eastern Europe, the question of God is more important than most people living in the West would imagine. One late autumn Adam and Maja presented us with a Christmas gift. Much to our surprise it was a szopka that they had brought back from Cracow, a colourful tinfoil model of the nativity scene set inside the entry of the Wawel Cathedral. This is a Polish folk art tradition in which people from all over the country compete for the best model. As they explained this tradition, they shared the place of Catholicism in their lives. At the time I did not feel the weight of this, and we were all aware that there was nothing comparable in our secular Parisian lives. Moreover, Adam was a self-described, failed Catholic, and often underscored his differences with organized religion. But to grasp the aspiration of his art, one must know that he was inhabited by a faith that modern reason has abandoned. In an interview some years later, I read Adam’s attempt to explain the resistance to his work that he encountered in France. He described a conversation with a French poet on a visit to Poland, who told him quite simply, "There is only one thing that astonishes me when I read Polish poetry. When I read your poems -not just yours - I see that you still have a problem with God. In France we decided it’s a childish question. It doesn’t exist." With typical wit Adam added, “I won’t tell you his name. Maybe he wouldn’t be saved." (Interview with Alice Quinn, 2009 The New Salon).

To make a portrait sculpture of a friend is an innocent pursuit, but not without risks. Rarely do we see others the way their loved ones see them. The time spent together, one contemplating the other, leads to a strange objectivity. It is very difficult to see clearly those to whom we are attached. We sometimes want things to be different from the way they are. And yet there is nothing like caring deeply to open up the senses and to feel we know things without knowing why.

Dear Jonathan,

Today I’m crying for Wojtek Pszoniak who just died. As you know, when you lose a friend there’s an avalanche of things that come to your mind.

I knew Wojtek for 70 years, he was like a brother for me.

I’ve read your essay on Milosz, I like it very much, you’ve found a way

to capture his essence not only in clay but also in words.

It’s a pity that we’ve lost contact years ago.

Let’s hope that--at least--we can be in touch through words. I

remember many beautiful moments in your study, with leafless trees

outside

or spring trees.

Love to all of your family,

Adam

Last March I received the news that Adam was very ill. Initially there were some grounds for hope, but within barely a few weeks it was over. Suddenly it was I, struggling to restore coherence to my own recollections as he gazed from a pedestal a few meters away. “Leafless trees outside / or spring trees” - this familiar hesitation and this nod to time - Adam’s voice.

I have become familiar with this feeling of irrevocable void, but nothing can compress the time it takes to absorb it. My first reflex was to go to the sculpture. When I looked into his eyes, they looked beyond me – or within himself - I couldn’t tell. I touched his cheeks, and imagined the air on his skin. I noticed his unusual ears. His tilted, slightly pursed mouth still amused me, and his large baldpate somehow did not age him. From today’s perspective he looked young. I could feel irony in the slant of his mouth and the corners where the lips fold inward, and even a hint of humour, but not enough to undermine his sincerity and serenity. I had made him slightly larger than life, perhaps to compensate for his shyness; unconsciously, I think, so he could hold his own next to my Milosz. I imagined the conversation we might have had, decades after having made this. “We always seek what is gone for good.” (Another Beauty)

We met toward the end of the eighties, less than ten years after he had arrived in Paris, and a few years after I had arrived from California. The collapse of the Soviet empire coincided with this period and several of our mutual friends came from Eastern Europe. To a degree that is difficult to imagine today, the times were optimistic. I was touched and amused when he described himself not as a political, but as an erotic, exile who had fled to Paris in pursuit of the woman he loved.

He lived with Maja in a comfortable flat on the western outskirts of the city. It was simple and tasteful, enough for the two of them as well as Maja’s daughter, but no more than that. Six for dinner was about the limit. There was a wall of books, and music, and photos, which spoke for themselves. Adam with Brodsky, Walcott, Strand, and of course Milosz. The contrast with Milosz struck me at the time, not only the difference in age, but also a difference in substance. Ann Kjellberg captured it vividly. "He had this eyebrow-cocked devilishness and puckish curiosity that danced a bit above their sometimes ponderous self-understandings. Shyness was perhaps a feature." (On Adam Zagajewski – Bookpost, 22 3 2021). Adam was emerging from the shadow of his elders, but, more critically, he was confronted with a different challenge. At a time of intense political change he resisted his Polish contemporaries who believed a writer with his gifts ought to put them in the service of his country, as he had already done very successfully while still in his twenties.

I am reminded of what I saw and felt when I made the sculpture. He looked shy, yet warm, quiet, solitary and contained, watchful, extremely sensitive; a certain stillness. Yet there was also a current of inner motion, as if I could feel his mind at work, or more precisely, his way of sensing the world. This became a conscious theme for the portrait – a state of receptivity and preparedness, even his skin needed to feel like an organ of the senses. Within his way of being I sensed a quiet, determined strength. It took me some time to grasp that this demeanor was a reflection of his conscious urge "to dissent from dissidents". He held true to his contemplative gaze and to an unabashed search for beauty; he could write of the ecstatic and he believed in the soul – this was the form of his resistance, more radical than it might appear. A dissident in the regime of post-modern decline, he wondered how the clay could take that on. And I thought to myself, only clay could take that on.

Adam’s relationship to those around him was complex. In a poem entitled Self-portrait he told us:

[…]

Sometimes in museums the paintings speak to me and irony suddenly vanishes.

I love gazing at my wife’s face.

Every Sunday I call my father.

Every other week I meet with friends,

thus proving my fidelity…

(from ‘Mysticism for Beginners’ 1997)

This felt like a confession and it surprised me, because Adam showed his fidelity in countless ways. Early on we had shared our appreciation for a proverb that we only knew in English, by Malebranche, a French eighteenth-century religious philosopher: "Attentiveness is the natural prayer of the soul." One day, out of the blue, a fax arrived from Houston with an affectionate note addressed to each of the three of us in my young family, along with a copy of the text in the French original. As I prepared to write this essay I discovered the fax folded into my copy of Mysticism for Beginners. Adam was aware that for us these were not idle words. Once Mariana bumped into him at a railway station, as she was accompanying our son to a school for children with special needs. Adam called out to Anton, whom he hardly knew, and embraced him with open arms, as if nothing could ever stand between them.

Adam Zagajewski, polychromed plaster (© Hirschfeld, 1990)

One day Adam asked if we could use my studio as the setting for a documentary about him to be filmed for German television. We had spent many hours together in this luminous space, working against the background chatter of chirping birds that he loved and recognized. There is a sequence in which he meanders through the atelier and settles on the small head of a young boy, for which he felt a particular affection. As I watch this video today I am reminded of his affirmation, with which he concluded his Neustadt lecture in 2004, that "innocence is perhaps the most daring thing in the entire world." The camera panned across the collection of portrait heads. Adam was among them. On the shelf they were all equals, memorable for the kind of human beings they were.

Adam’s thoughts could take you from Las Meninas in the Prado to Balthus, from Bach to Mahler, sharing his enthusiasms. Yet he was not a snob: "French intellectuals love to look down their noses at Americans and their boorishness, their lack of taste. France …. frequently fails to understand American enthusiasm. An example: once I was standing before one of the Vermeers in Washington’s National Gallery. An American, about forty years old, stood beside me. At one point he turned to me and said (his voice trembled with joy), ‘I’ve been looking at reproductions of this painting since I was twenty, and today I am seeing with my own eyes for the first time. I’m sorry to bother you, but I had to tell someone.’ I can take such lack of culture any day." (Another Beauty)

Once Adam began a university talk with a quotation affirming "It is certainly not the mission of the mind to defend the world dominance of money. Hardly any system was so detrimental to the basic human values as that of capitalism." After describing the police state in which he grew up, he showed his hand. "I hope I have sketched the epistemological situation of someone living in a Communist country clearly enough. And even if this someone – that is, me – would be inclined to adopt a rather aristocratic perspective and to pay homage to artistic and religious imagination rather than to the rules of the free market, he would find it difficult to forget and to renounce his totalitarian experience. Therefore I have no intention of repudiating my old affinity to the human reality as it was described by Balzac. I think I can reveal now that I do not agree with the thesis expressed by Erich Kahler. Yes, it is the mission of the human mind to defend money and the market economy, though it should not be its exclusive and uncritical mission." Adam was his own man.

Expatriates from Eastern Europe were clearly different from their counterparts from North America. Similar things may have enchanted us - the miracle of post-war Western Europe was something to behold - but behind each of us were continents of unshared experience. « The West Berlin of the early eighties struck me as a peculiar synthesis of the Old Prussian capital and a frivolous city fascinated by Manhattan and the avant-garde (sometimes I suspected that the local intellectuals and artists treated the wall as yet another invention of Marcel Duchamp)”. (A Defence of Ardour)

When Adam laughed it was as if he was bubbling up from within, literally tickled by his own thoughts. "I don’t see any fundamental contradiction between humour and mystical experience; both serve to wrench us out of our immediate, given reality." (A Defence of Ardour) I recall a dinner when my wife was bursting with our unborn son. A home video shows Adam playfully tasting the stuffed cabbage and entertaining us with a humorous account of the American feminists that he had only recently discovered in Houston, Texas. As I remember his laughter, I struggle to come to terms with the photos of a much older gentleman that illustrate the eulogies in his memory. Time itself had sculpted my friend. He had matured, and handsomely, but I was grateful to have caught him at a stage when he was still becoming.

Sometimes I felt that Adam and I were like animals from different species that happened to meet by the same river, propelled by a similar thirst. Neither of us had come to Paris by accident but we were bound there, more deeply by love for a person than by love for the place. This made for a mostly unspoken understanding. During one long walk through the city I recall discussing a theme that affected each of us in different ways, the impossibility of witnessing an artist at work. In a conversation with Edward Hirsch he comments on his friendship with Zbigniew Herbert; "…but we never actually see the person in poetic action, there is this hidden life of the poet, there is something so shameful, or at least very discrete in the poet who is in the act of writing, or inspiration… you never see it. So these friendships are not touching upon the deeper layer…", (https://podcast.lannan.org/2009/07/09/adam-zagajewski-with-edward-hirsch/) In a poem entitled “Poets Photographed”, Adam observed that photographs never show the poets "when they truly see”, “never in darkness, never in silence”, “at night, in uncertainty, when they hesitate, when joy, like phosphorus, clings to matches."

The human face is our first landscape. It offers wholeness and unity, even as the idea of the singular human personality has been slowly disintegrating for more than a century. Inner awareness and inner gaze matter as much as the way a person attends to the outside world. The common denominator is consciousness. Often I am trying to reveal something in my portraits that I cannot so much see, as feel. We tend to put the emphasis on vision, as if the key to the art of portraiture is the accuracy of the record. Technique is imitable, but not the synthesis. True essence lies in empathy, the only channel that can reveal the invisible.

For many in Eastern Europe, the question of God is more important than most people living in the West would imagine. One late autumn Adam and Maja presented us with a Christmas gift. Much to our surprise it was a szopka that they had brought back from Cracow, a colourful tinfoil model of the nativity scene set inside the entry of the Wawel Cathedral. This is a Polish folk art tradition in which people from all over the country compete for the best model. As they explained this tradition, they shared the place of Catholicism in their lives. At the time I did not feel the weight of this, and we were all aware that there was nothing comparable in our secular Parisian lives. Moreover, Adam was a self-described, failed Catholic, and often underscored his differences with organized religion. But to grasp the aspiration of his art, one must know that he was inhabited by a faith that modern reason has abandoned. In an interview some years later, I read Adam’s attempt to explain the resistance to his work that he encountered in France. He described a conversation with a French poet on a visit to Poland, who told him quite simply, "There is only one thing that astonishes me when I read Polish poetry. When I read your poems -not just yours - I see that you still have a problem with God. In France we decided it’s a childish question. It doesn’t exist." With typical wit Adam added, “I won’t tell you his name. Maybe he wouldn’t be saved." (Interview with Alice Quinn, 2009 The New Salon).

To make a portrait sculpture of a friend is an innocent pursuit, but not without risks. Rarely do we see others the way their loved ones see them. The time spent together, one contemplating the other, leads to a strange objectivity. It is very difficult to see clearly those to whom we are attached. We sometimes want things to be different from the way they are. And yet there is nothing like caring deeply to open up the senses and to feel we know things without knowing why.

This article is taken from PN Review 263, Volume 48 Number 3, January - February 2022.