This article is taken from PN Review 261, Volume 48 Number 1, September - October 2021.

Pictures from a Library

Pictures from the Rylands Library

‘A Life Beyond Life’ in the Book of the Dead

Books, according to John Milton, contain ‘a potency of life… as active as that soul whose progeny they are’. They ‘preserve as in a vial the pure efficacy and extraction of that living intellect that bred them’. They are ‘the master spirit embalm’d and treasur’d up on purpose to a life beyond life’. In other words books never die for they are ‘as living in the minds or thoughts of readers, literally inhabiting the minds of others… in the readerly mind rethought’ (Andrew Bennett).

Putting to one side the fact that the Book of the Dead shown here is the product of an entire culture rather than an individual, an ancient Egyptian might have felt Milton’s vision of a book’s power to ensure a ‘life beyond life’ a failure of ambition. For this ‘book’, a collection of magical spells, in the form of a hieroglyphic scroll written on papyrus by an unknown hand long before the Common Era, is designed as a practical guide. Its aim was to assist the deceased owner avoid the hazards of their journey through the afterlife so they could be ‘absorbed in the great rhythm of the universe’ for all eternity (H. Frankfort).

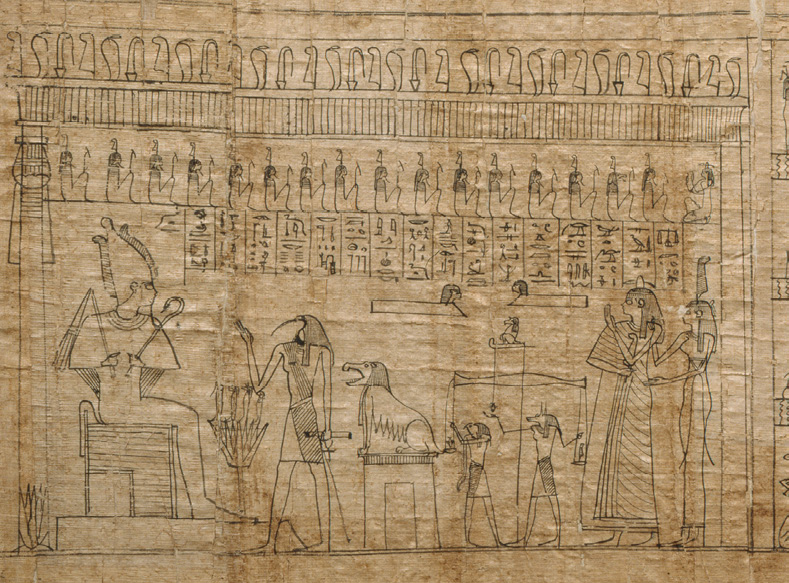

But before the deceased could embark upon their quest they first had to undergo the trial of a Second Death known as the Weighing of the Heart Ceremony shown above. At the centre of this cosmic drama Maat, goddess of truth (identified by a feather) presents the deceased to Osiris, the god of life, death and regeneration. As the deceased’s heart is weighed against Maat’s feather the jackal-headed Anubis (god of mummification) and falcon-headed Horus, whose Eye offers protection to all Egyptians, ensure the proper working order of the scales, while forty-two assessors observe proceedings from their niches above. If the deceased’s heart proves heavier than Matt’s feather it will be thrown into the crocodile jaws of the demon/goddess Ammut who will devour it, casting the deceased into oblivion for all time, obliterating all memory of their existence (E. Hornung).

The outcome would hang in the balance were it not for the fact that Ibis-headed Thoth, scribe of the gods, clutches a life-giving ‘ankh’ sign and his hieroglyphic script shows the tipping of scales in favour of the deceased’s lighter-than-featherweight heart. For the Ancient Egyptians believed (so we believe) that words and books had agency to control, as well as to preserve. And as the words of the gods (‘mdw-ntr’) they held power over events and destinies (Hornung) to create not one but many lives beyond life.

This article is taken from PN Review 261, Volume 48 Number 1, September - October 2021.