This article is taken from PN Review 257, Volume 47 Number 3, January - February 2021.

Against Oblivion

Some individuals grow in significance as they recede in time. The veneration that is evident in virtually every account of Czesław Miłosz testifies to this phenomenon, so much so that writing about his portrait has been daunting.

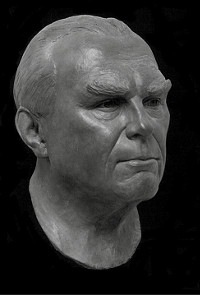

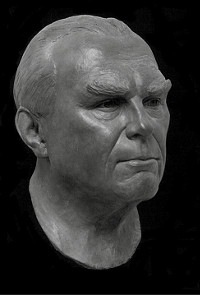

The idea to make the portrait was born when I attended a reading at the University of California in Los Angeles in 1982. The room was packed and worshipful. Virtually all of his writing was in Polish, which most in the audience, including myself, would never know except in translation. First, he read in his native tongue, then in English. I recall sensing the paradox of a soft melodious voice that could create a feeling of great closeness while preserving a palpable distance. I knew some of his poetry and a number of his essays and recognised the unmistakable rhythm of his language. Robert Hass, his principle collaborator and translator, has described his ‘fierce, hawkish, standoffish formality’. Even allowing for the animated eyes and mischievous smile, he seemed the incarnation of gravity and dignity. His large, wide face, with its strong planes, forceful jaw, and unforgettable brows, recalled a medieval wood carved saint.

No doubt it was the legend that shaped my initial impressions. His book, The Captive Mind, published in the early 1950s in Paris after his defection from Stalinist Poland, revealed the psychology and destiny of intellectuals complicit with the regime. Bells in Winter was my first encounter with his poetry, in which I learned of his concern for philosophical and spiritual matters that went far beyond politics. Yet it was his destiny to wrestle with his beliefs, and to write poetry, within earshot of some of the greatest horrors of the twentieth century. Thanks to several of those poems, Miłosz had become an iconic Christian witness to the devastation of World War II. When he was awarded the Nobel Prize for literature in 1980, almost instantly he became the voice of Solidarity, the first independent labour movement in a Soviet bloc country. Miłosz had cut a solitary path through the minefields of the twentieth century and fought against the over simplifications that inevitably followed upon the Nobel Prize. ‘Out of these ashes emerged poetry which did not so much sing of outrage and grief as whisper of the guilt of the survivor.’ (Brodsky). He would not be defined solely by his defection from Communist Poland.

For a celebrated writer in exile to declare ‘language is the only homeland’ is both a triumph and a confession of loss, and this loss fuelled his commitment to the primary importance of historical memory. Ten years prior to the collapse of the Soviet Union, from the platform afforded by the Nobel Prize, Miłosz reminded the world of the millions of forgotten victims of twentieth-century totalitarianism, as well as of the nations that remained imprisoned under communism, many decades after the end of World War II. He lamented the amnesia of ‘modern illiterates’ for whom ‘history is present but blurred, in a state of strange confusion’. Commenting on Holocaust deniers, he warned, ‘If such insanity is possible, is a complete loss of memory as a permanent state of mind improbable? And would it not present a danger more grave than genetic engineering or poisoning of the natural environment?’

During that reading at UCLA I was aware that with his Slavic features and his princely bearing he was the embodiment of a culture, which I understood only vaguely. I knew little about Poland beyond the tragedy of the Jews; however, his definition of poetry as the ‘passionate pursuit of the real’ resonated deeply. I understood my own task in portraiture in precisely such terms, and wondered if it had ever occurred to him that at some point he was destined to become the object of such a pursuit, even if by temperament he was a very private man. I could imagine the portrait I might make. I simply had no clue how that might come to pass.

It is said that in dreams begin responsibilities. Less than ten years later I became friends with a group of writers in Paris, which included Adam Zagajewski, a renowned Polish poet of the next generation who was close to Miłosz. Adam came to know my work and agreed to help me approach Miłosz. With no more than an introduction from Adam, my own admiration and a heavy dose of chutzpah, I drove with my wife from Los Angeles to his home on Grizzly Peak in Berkeley in the hope of convincing Miłosz to sit for me. He was a vigorous eighty year old, and could still negotiate the winding path among magnificent trees down to his home over-looking San Francisco Bay. The greeting was friendly, and from the start I felt that he and his future wife Carole were sympathetic to the idea.

I recall showing them pictures of my portrait sculpture, and dwelling particularly on the bronze head of Eric Hoffer, the longshoreman-philosopher that I had made from life in 1979. Hoffer’s classic book The True Believer (1951), about the psychology of mass movements, is often found on the same bookshelf as The Captive Mind. Their perspectives were very different, but I assumed that Hoffer, who had lived barely twenty miles away, would have been of interest to Miłosz. After being escorted by Hoffer around San Francisco in 1955, Hannah Arendt herself had written ‘his kind of person is simply the best thing this country has to offer.’ (1955 letter to Karl Jaspers). As it stands, the only place that the ‘fastidious and aristocratic’ descendant of the Polish gentry was ever to encounter the self-made, working-class, American thinker was in my studio, each silent in his own world. Some years later, when I read that Miłosz had more ‘respect for hardworking lumberjacks, miners, bus drivers, bricklayers, whose mentality arouses scorn in the young’ (San Francisco Chronicle 26/3/2006, Cynthia Haven) I felt still more strongly that an opportunity had been missed. In that first meeting, I had convinced Miłosz of my ability, but remained unsure that I would know how to engage him.

When I look at the photographs taken in his garden overlooking San Francisco Bay he appears surprisingly uncomfortable and uncooperative. I explained that this would be a collaborative effort, of a kind, and photographs would be no substitute for time spent together. He would have to sit with me for a couple of hours at a time, every day, over a period of a week or so. Usually I would expect to take at least twice that, but this already felt like a considerable imposition. When we began to consider where I might actually do my work it appeared that whatever reluctance he might have felt had been overcome. It would have to be a place close by, from where he could easily come and go, and where I could continue on my own, without disrupting his routine. His garage was at some remove from the house, at the top of the path leading to the street, behind which there was a small guest studio where I would be able to take breaks. The garage was dark, musty and encumbered, but it would have to do. They invited me to return in six months.

*

In preparation for the trip north, in the early summer of 1990, I bundled my clay, my tools, and my modelling stand into the trunk, and thought about the man on Grizzly Peak. Since that reading in Los Angeles, Miłosz had lost his first wife, Janka, and a more sustained return to Poland was now on the horizon. For most of his life no one, least of all ‘the Wrong Honorable Professor Milosz [sic], Who wrote poems in some unheard of tongue’, would have imagined his future status. Except for Janka, who foresaw the Nobel Prize. What I did not know, as I anticipated the meeting ahead, was the degree of his personal torment. For many years she had struggled with a debilitating disease, and his younger son suffered from mental illness. In a personal letter to his biographer, that I only recently discovered, he wrote ‘I only bow and smile like a puppet, maintain a mask, while inside me there is suffering and great distress.’ This was the man whom I had first seen in Los Angeles eight years before. In his memoir, The Year of The Hunter (1994), he concluded his description of his wife’s physical and mental deterioration with this startling, simple sentence, reminiscent of Haiku: ‘The Nobel Prize, when it came, was, for her, a tragedy.’

Reverberating through the austere expanse of the San Fernando Valley as I drove north, I could almost hear his description of California as the ‘elixir of alienation’. The vast American West could not have been more different from the scale of Europe, with its intimate tapestry of habitats and traditions knitted together over centuries. ‘I seek shelter in these pages, but my humanistic zeal has been weakened by the mountains and the ocean, by those many moments when I have gazed upon boundless immensities with a feeling akin to nausea, the wind ravaging my little homestead of hopes and intentions’ (Visions From San Francisco Bay).

In contrast to the grandeur of the scenery the setting for my work was almost comical in its modesty. I imagined the sculptor Houdon, face to face with his eighteenth-century luminaries, and ignoring the beaten up couch in the corner, the broken lamps and the clutter of boxes piled up on my right, I concentrated on the monumental personality before me. Miłosz sat on a high, backed bar stool draped with an old sheet, raised up on a platform I had cobbled together with materials from a local hardware store. Initially I could feel his effort, his formality and his reserve – his sense of self was palpable. Just as he had taken a stand against poetry that turned inward toward private emotions, his discretion with respect to personal matters was absolute and there was little small talk. I couldn’t shake the feeling that while he was certainly there by choice, somehow I was still an intruder. I felt I had been invited to look, even to scrutinise, but perhaps not to see. There is a photo taken after I had already developed a good rough sketch in clay, which shows him good humoured, suggesting that as he gained confidence in the outcome he began to relax. But he made no comments on the process. After the first session he invited me to join him in his ritual vodka, and was disappointed to discover that I did not share his drinking habits. No doubt it would have been much better had I been able to take him up on it, but I would never have made it through the week. By temperament Miłosz was cool, and proud, but he could also display a despairing cheerfulness. When he smiled, he would pause to make sure that I was with him. If one had to pick an expression by which to remember Miłosz it would not be a smile of joy, nor even his ironic one, although I saw both. I hoped those qualities might somehow be felt in the work, as a potential.

In order to witness different aspects of his personality we needed to talk. To bore him would have been fatal. Despite the difference in age, my education was broader than he expected and this mattered to him. I knew of his struggles with French intellectuals enamoured of Stalin and had read widely among the veterans of those battles. He was not at peace with many things about the West, and the questions posed by Marxism and religion weighed on him. He didn’t try to test me, but I could feel his immense culture and my own limitations. From the point of view of my task, such exchanges mattered primarily for the way they revealed his expressions, and his resistance to many facets of the modern world seemed inscribed in his features. My efforts to underscore something of my understanding of the twentieth century led to an exchange that I shall never forget. I inquired about the Polish officers massacred by the Soviets at Katyn and framed my question in such a way as to suggest a comparison between their brutality and the Nazis. Miłosz replied, in the spirit of a naturalist and a moral philosopher, that if one had a choice, a bullet in the neck would be preferable to the gas chamber. His cool lucidity, expressed not just in words, but also in his gaze, left me with a feeling that my effort to find common ground had been a betrayal of memory.

Despite this admonishment, Miłosz did not feel like a stranger. As long as I can remember I had heard English spoken with accents from Western and Eastern Europe, with intonations that I felt I could almost smell. The experience of devastation, exile and lost roots were familiar themes in my family and among my closest friends. My father, two years younger than Miłosz, had escaped Berlin in 1936. One of his first journeys after the wall came down was to East Berlin to visit the gravesite of his grandparents, and to visit sections of the city that he had not seen in over half a century. I had gone with him. My father-in-law travelled to Romania as soon as he could, in a similar spirit, and spent the last decades of his life living between a lost world reborn and the West, where he never fully adjusted. It would be presumptuous to say that I understood Miłosz, but I felt intuitively that I knew something of the forces that had shaped him. When he made a point of telling me that I was a warm man, I sensed that he was responding to this feeling, although afterward I remember wondering if there was not also a hint of irony in his comment. He knew much less about me than I knew about him, and I knew he liked to quote Heraclitus, ‘that dry souls are the best…’

*

And form itself as always is a betrayal – Miłosz

I have now read about many encounters with Miłosz and many descriptions of his manner. About his remoteness, his warmth, his humour, even his shyness, his impatience, his anger, his resilience, his complexity, his doubts, the force of his words, written when no words were thought possible, his presence. My goal was a synthesis, a kind of summing up, not any one moment, and certainly nothing that one pose could possibly contain. During my time with him I watched as intently as I could, scrutinising every detail, absorbing every shifting mood, reaching for something as unachievable, as metaphysically impossible, as the quest that he himself had defined as the poet’s relationship to reality. However, one must earn one’s discontent. One first must notice the weight of the jaw, the extreme particularity of each feature, the breadth and slope of the forehead, the curl of the lips and the swelling of the planes, the folds around the eyes, the quality of the hair, the telling asymmetries that convey the complexity of the emotions and intellect; one must travel again and again this unique terrain until in the mind’s eye, at night while the clay sleeps, one can feel the entire head as one complex mass, with a structure and a thrust, and tilt belonging to this person alone. When you have done that, you have earned the right to say that something is still missing.

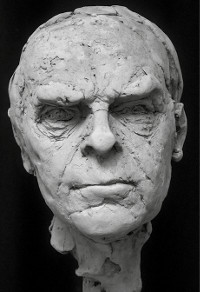

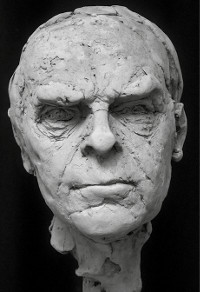

Several years later I learned that Miłosz was going to be in Paris, and we spent another few hours in my studio. We shared the feeling that there were other possibilities, something less formal, and more mobile than the Berkeley version. This was the first time he would be in my environment and I was looking forward to it. My recently completed Fragment of Heraclitus in translucent marble was on display. The interpretation of Heraclitus was intentionally ambiguous – a deliberate play on masculine and feminine traits. Knowing his own interest in the philosopher, I was eager to share my vision. His summary reaction caught me completely unprepared. ‘Why did you make him queer?’ he asked bluntly, so sure he was commenting on an objective fact, without taking into account the eye of the beholder. In subsequent years this episode stayed with me. Why, I wondered, the simplistic reading?

Over the years my doubts about my portrait also lingered. When I began to write this essay I discovered a substantial collection of photographs on the Internet. When I found the photograph of the young Miłosz, it was as if I had found the tender acorn to the formidable oak that I had portrayed in Berkeley, a glimpse of the extreme sensitivity matched by strength, soulfulness allied with intensity of mind, inner search married to practical resolve with which he had started out in life. I pondered the fact that something about his mouth, and also the eyes, reminded me of my Heraclitus.

The version of Miłosz I made in Paris was more than a sketch, and less than a finished work. It is filled with knotted intensity, rough, unfinished forms and the traces of accident. In ‘Ars Poetica’ (Bells In Winter) Miłosz wrote – ‘The purpose of poetry is to remind us how difficult it is to remain just one person, for our house is open, there are no keys in the doors, and invisible guests come in and out at will.’ – By his own account he was ‘neither noble nor simple’. He had cautioned an interviewer ‘Art is not a sufficient substitute for the problem of leading a moral life. I am afraid of wearing a cloak that is too big for me’ (Czesław Miłosz, 1994, Interviewed by Robert Faggen). I knew there was truth in the dry, raw clay of the second version, and it felt right that it should remain just this way.

Miłosz taught that what is not written down will be forgotten. He inscribed several of his books with words of encouragement, of hope that we could continue. At the conclusion to the sittings, he said little. An empty envelope leaves me bewildered that a letter from him could possibly go missing. In the sphere of remembrance the tradition of portraiture mediates between truth and legend. Perhaps the problem was the pedestal. Perhaps, to be immortalised in this time-honoured tradition, that had lost its footing in the twentieth century along with so much else, was not for Miłosz. Fortunately, it was not up to him.

Epilogue

I never know what to expect when I invite someone into my studio for the first time. In this case the fellow was an aspiring novelist. Judging from the way he looked he came from someplace in South Asia, but he turned out to have been born and bred in England. When I told him that I liked to work with writers, he was curious. As a man in his early forties I did not imagine that he would necessarily know the ones who had sat for me, but I found him interesting, with his Sri Lankan heritage, his impeccable accent, his Buddhist inclinations and his choice to settle with his young family in France. I invited him to come by. No sooner had he crossed the threshold, when he zeroed in on the dry clay unfinished portrait commanding a corner of my crowded studio, and exclaimed, ‘That’s Miłosz!’ In the stillness, taking a moment to absorb the effigy, he began reciting from the first Miłosz poem he had learned in high school, ‘It seems I was called for this: To glorify things just because they are.’

The idea to make the portrait was born when I attended a reading at the University of California in Los Angeles in 1982. The room was packed and worshipful. Virtually all of his writing was in Polish, which most in the audience, including myself, would never know except in translation. First, he read in his native tongue, then in English. I recall sensing the paradox of a soft melodious voice that could create a feeling of great closeness while preserving a palpable distance. I knew some of his poetry and a number of his essays and recognised the unmistakable rhythm of his language. Robert Hass, his principle collaborator and translator, has described his ‘fierce, hawkish, standoffish formality’. Even allowing for the animated eyes and mischievous smile, he seemed the incarnation of gravity and dignity. His large, wide face, with its strong planes, forceful jaw, and unforgettable brows, recalled a medieval wood carved saint.

No doubt it was the legend that shaped my initial impressions. His book, The Captive Mind, published in the early 1950s in Paris after his defection from Stalinist Poland, revealed the psychology and destiny of intellectuals complicit with the regime. Bells in Winter was my first encounter with his poetry, in which I learned of his concern for philosophical and spiritual matters that went far beyond politics. Yet it was his destiny to wrestle with his beliefs, and to write poetry, within earshot of some of the greatest horrors of the twentieth century. Thanks to several of those poems, Miłosz had become an iconic Christian witness to the devastation of World War II. When he was awarded the Nobel Prize for literature in 1980, almost instantly he became the voice of Solidarity, the first independent labour movement in a Soviet bloc country. Miłosz had cut a solitary path through the minefields of the twentieth century and fought against the over simplifications that inevitably followed upon the Nobel Prize. ‘Out of these ashes emerged poetry which did not so much sing of outrage and grief as whisper of the guilt of the survivor.’ (Brodsky). He would not be defined solely by his defection from Communist Poland.

For a celebrated writer in exile to declare ‘language is the only homeland’ is both a triumph and a confession of loss, and this loss fuelled his commitment to the primary importance of historical memory. Ten years prior to the collapse of the Soviet Union, from the platform afforded by the Nobel Prize, Miłosz reminded the world of the millions of forgotten victims of twentieth-century totalitarianism, as well as of the nations that remained imprisoned under communism, many decades after the end of World War II. He lamented the amnesia of ‘modern illiterates’ for whom ‘history is present but blurred, in a state of strange confusion’. Commenting on Holocaust deniers, he warned, ‘If such insanity is possible, is a complete loss of memory as a permanent state of mind improbable? And would it not present a danger more grave than genetic engineering or poisoning of the natural environment?’

During that reading at UCLA I was aware that with his Slavic features and his princely bearing he was the embodiment of a culture, which I understood only vaguely. I knew little about Poland beyond the tragedy of the Jews; however, his definition of poetry as the ‘passionate pursuit of the real’ resonated deeply. I understood my own task in portraiture in precisely such terms, and wondered if it had ever occurred to him that at some point he was destined to become the object of such a pursuit, even if by temperament he was a very private man. I could imagine the portrait I might make. I simply had no clue how that might come to pass.

It is said that in dreams begin responsibilities. Less than ten years later I became friends with a group of writers in Paris, which included Adam Zagajewski, a renowned Polish poet of the next generation who was close to Miłosz. Adam came to know my work and agreed to help me approach Miłosz. With no more than an introduction from Adam, my own admiration and a heavy dose of chutzpah, I drove with my wife from Los Angeles to his home on Grizzly Peak in Berkeley in the hope of convincing Miłosz to sit for me. He was a vigorous eighty year old, and could still negotiate the winding path among magnificent trees down to his home over-looking San Francisco Bay. The greeting was friendly, and from the start I felt that he and his future wife Carole were sympathetic to the idea.

I recall showing them pictures of my portrait sculpture, and dwelling particularly on the bronze head of Eric Hoffer, the longshoreman-philosopher that I had made from life in 1979. Hoffer’s classic book The True Believer (1951), about the psychology of mass movements, is often found on the same bookshelf as The Captive Mind. Their perspectives were very different, but I assumed that Hoffer, who had lived barely twenty miles away, would have been of interest to Miłosz. After being escorted by Hoffer around San Francisco in 1955, Hannah Arendt herself had written ‘his kind of person is simply the best thing this country has to offer.’ (1955 letter to Karl Jaspers). As it stands, the only place that the ‘fastidious and aristocratic’ descendant of the Polish gentry was ever to encounter the self-made, working-class, American thinker was in my studio, each silent in his own world. Some years later, when I read that Miłosz had more ‘respect for hardworking lumberjacks, miners, bus drivers, bricklayers, whose mentality arouses scorn in the young’ (San Francisco Chronicle 26/3/2006, Cynthia Haven) I felt still more strongly that an opportunity had been missed. In that first meeting, I had convinced Miłosz of my ability, but remained unsure that I would know how to engage him.

When I look at the photographs taken in his garden overlooking San Francisco Bay he appears surprisingly uncomfortable and uncooperative. I explained that this would be a collaborative effort, of a kind, and photographs would be no substitute for time spent together. He would have to sit with me for a couple of hours at a time, every day, over a period of a week or so. Usually I would expect to take at least twice that, but this already felt like a considerable imposition. When we began to consider where I might actually do my work it appeared that whatever reluctance he might have felt had been overcome. It would have to be a place close by, from where he could easily come and go, and where I could continue on my own, without disrupting his routine. His garage was at some remove from the house, at the top of the path leading to the street, behind which there was a small guest studio where I would be able to take breaks. The garage was dark, musty and encumbered, but it would have to do. They invited me to return in six months.

In preparation for the trip north, in the early summer of 1990, I bundled my clay, my tools, and my modelling stand into the trunk, and thought about the man on Grizzly Peak. Since that reading in Los Angeles, Miłosz had lost his first wife, Janka, and a more sustained return to Poland was now on the horizon. For most of his life no one, least of all ‘the Wrong Honorable Professor Milosz [sic], Who wrote poems in some unheard of tongue’, would have imagined his future status. Except for Janka, who foresaw the Nobel Prize. What I did not know, as I anticipated the meeting ahead, was the degree of his personal torment. For many years she had struggled with a debilitating disease, and his younger son suffered from mental illness. In a personal letter to his biographer, that I only recently discovered, he wrote ‘I only bow and smile like a puppet, maintain a mask, while inside me there is suffering and great distress.’ This was the man whom I had first seen in Los Angeles eight years before. In his memoir, The Year of The Hunter (1994), he concluded his description of his wife’s physical and mental deterioration with this startling, simple sentence, reminiscent of Haiku: ‘The Nobel Prize, when it came, was, for her, a tragedy.’

Reverberating through the austere expanse of the San Fernando Valley as I drove north, I could almost hear his description of California as the ‘elixir of alienation’. The vast American West could not have been more different from the scale of Europe, with its intimate tapestry of habitats and traditions knitted together over centuries. ‘I seek shelter in these pages, but my humanistic zeal has been weakened by the mountains and the ocean, by those many moments when I have gazed upon boundless immensities with a feeling akin to nausea, the wind ravaging my little homestead of hopes and intentions’ (Visions From San Francisco Bay).

In contrast to the grandeur of the scenery the setting for my work was almost comical in its modesty. I imagined the sculptor Houdon, face to face with his eighteenth-century luminaries, and ignoring the beaten up couch in the corner, the broken lamps and the clutter of boxes piled up on my right, I concentrated on the monumental personality before me. Miłosz sat on a high, backed bar stool draped with an old sheet, raised up on a platform I had cobbled together with materials from a local hardware store. Initially I could feel his effort, his formality and his reserve – his sense of self was palpable. Just as he had taken a stand against poetry that turned inward toward private emotions, his discretion with respect to personal matters was absolute and there was little small talk. I couldn’t shake the feeling that while he was certainly there by choice, somehow I was still an intruder. I felt I had been invited to look, even to scrutinise, but perhaps not to see. There is a photo taken after I had already developed a good rough sketch in clay, which shows him good humoured, suggesting that as he gained confidence in the outcome he began to relax. But he made no comments on the process. After the first session he invited me to join him in his ritual vodka, and was disappointed to discover that I did not share his drinking habits. No doubt it would have been much better had I been able to take him up on it, but I would never have made it through the week. By temperament Miłosz was cool, and proud, but he could also display a despairing cheerfulness. When he smiled, he would pause to make sure that I was with him. If one had to pick an expression by which to remember Miłosz it would not be a smile of joy, nor even his ironic one, although I saw both. I hoped those qualities might somehow be felt in the work, as a potential.

In order to witness different aspects of his personality we needed to talk. To bore him would have been fatal. Despite the difference in age, my education was broader than he expected and this mattered to him. I knew of his struggles with French intellectuals enamoured of Stalin and had read widely among the veterans of those battles. He was not at peace with many things about the West, and the questions posed by Marxism and religion weighed on him. He didn’t try to test me, but I could feel his immense culture and my own limitations. From the point of view of my task, such exchanges mattered primarily for the way they revealed his expressions, and his resistance to many facets of the modern world seemed inscribed in his features. My efforts to underscore something of my understanding of the twentieth century led to an exchange that I shall never forget. I inquired about the Polish officers massacred by the Soviets at Katyn and framed my question in such a way as to suggest a comparison between their brutality and the Nazis. Miłosz replied, in the spirit of a naturalist and a moral philosopher, that if one had a choice, a bullet in the neck would be preferable to the gas chamber. His cool lucidity, expressed not just in words, but also in his gaze, left me with a feeling that my effort to find common ground had been a betrayal of memory.

Despite this admonishment, Miłosz did not feel like a stranger. As long as I can remember I had heard English spoken with accents from Western and Eastern Europe, with intonations that I felt I could almost smell. The experience of devastation, exile and lost roots were familiar themes in my family and among my closest friends. My father, two years younger than Miłosz, had escaped Berlin in 1936. One of his first journeys after the wall came down was to East Berlin to visit the gravesite of his grandparents, and to visit sections of the city that he had not seen in over half a century. I had gone with him. My father-in-law travelled to Romania as soon as he could, in a similar spirit, and spent the last decades of his life living between a lost world reborn and the West, where he never fully adjusted. It would be presumptuous to say that I understood Miłosz, but I felt intuitively that I knew something of the forces that had shaped him. When he made a point of telling me that I was a warm man, I sensed that he was responding to this feeling, although afterward I remember wondering if there was not also a hint of irony in his comment. He knew much less about me than I knew about him, and I knew he liked to quote Heraclitus, ‘that dry souls are the best…’

And form itself as always is a betrayal – Miłosz

I have now read about many encounters with Miłosz and many descriptions of his manner. About his remoteness, his warmth, his humour, even his shyness, his impatience, his anger, his resilience, his complexity, his doubts, the force of his words, written when no words were thought possible, his presence. My goal was a synthesis, a kind of summing up, not any one moment, and certainly nothing that one pose could possibly contain. During my time with him I watched as intently as I could, scrutinising every detail, absorbing every shifting mood, reaching for something as unachievable, as metaphysically impossible, as the quest that he himself had defined as the poet’s relationship to reality. However, one must earn one’s discontent. One first must notice the weight of the jaw, the extreme particularity of each feature, the breadth and slope of the forehead, the curl of the lips and the swelling of the planes, the folds around the eyes, the quality of the hair, the telling asymmetries that convey the complexity of the emotions and intellect; one must travel again and again this unique terrain until in the mind’s eye, at night while the clay sleeps, one can feel the entire head as one complex mass, with a structure and a thrust, and tilt belonging to this person alone. When you have done that, you have earned the right to say that something is still missing.

Several years later I learned that Miłosz was going to be in Paris, and we spent another few hours in my studio. We shared the feeling that there were other possibilities, something less formal, and more mobile than the Berkeley version. This was the first time he would be in my environment and I was looking forward to it. My recently completed Fragment of Heraclitus in translucent marble was on display. The interpretation of Heraclitus was intentionally ambiguous – a deliberate play on masculine and feminine traits. Knowing his own interest in the philosopher, I was eager to share my vision. His summary reaction caught me completely unprepared. ‘Why did you make him queer?’ he asked bluntly, so sure he was commenting on an objective fact, without taking into account the eye of the beholder. In subsequent years this episode stayed with me. Why, I wondered, the simplistic reading?

Over the years my doubts about my portrait also lingered. When I began to write this essay I discovered a substantial collection of photographs on the Internet. When I found the photograph of the young Miłosz, it was as if I had found the tender acorn to the formidable oak that I had portrayed in Berkeley, a glimpse of the extreme sensitivity matched by strength, soulfulness allied with intensity of mind, inner search married to practical resolve with which he had started out in life. I pondered the fact that something about his mouth, and also the eyes, reminded me of my Heraclitus.

The version of Miłosz I made in Paris was more than a sketch, and less than a finished work. It is filled with knotted intensity, rough, unfinished forms and the traces of accident. In ‘Ars Poetica’ (Bells In Winter) Miłosz wrote – ‘The purpose of poetry is to remind us how difficult it is to remain just one person, for our house is open, there are no keys in the doors, and invisible guests come in and out at will.’ – By his own account he was ‘neither noble nor simple’. He had cautioned an interviewer ‘Art is not a sufficient substitute for the problem of leading a moral life. I am afraid of wearing a cloak that is too big for me’ (Czesław Miłosz, 1994, Interviewed by Robert Faggen). I knew there was truth in the dry, raw clay of the second version, and it felt right that it should remain just this way.

Miłosz taught that what is not written down will be forgotten. He inscribed several of his books with words of encouragement, of hope that we could continue. At the conclusion to the sittings, he said little. An empty envelope leaves me bewildered that a letter from him could possibly go missing. In the sphere of remembrance the tradition of portraiture mediates between truth and legend. Perhaps the problem was the pedestal. Perhaps, to be immortalised in this time-honoured tradition, that had lost its footing in the twentieth century along with so much else, was not for Miłosz. Fortunately, it was not up to him.

Epilogue

I never know what to expect when I invite someone into my studio for the first time. In this case the fellow was an aspiring novelist. Judging from the way he looked he came from someplace in South Asia, but he turned out to have been born and bred in England. When I told him that I liked to work with writers, he was curious. As a man in his early forties I did not imagine that he would necessarily know the ones who had sat for me, but I found him interesting, with his Sri Lankan heritage, his impeccable accent, his Buddhist inclinations and his choice to settle with his young family in France. I invited him to come by. No sooner had he crossed the threshold, when he zeroed in on the dry clay unfinished portrait commanding a corner of my crowded studio, and exclaimed, ‘That’s Miłosz!’ In the stillness, taking a moment to absorb the effigy, he began reciting from the first Miłosz poem he had learned in high school, ‘It seems I was called for this: To glorify things just because they are.’

Images

- Czesław Miłosz, polychromed plaster, life size (© Hirschfeld, 1990)

- Czesław Miłosz, dry clay, life size (© Hirschfeld, 1993)

- Czesław Miłosz as a young man (© http://muzeumliteratury.pl/wp-content/uploads/2011/02/Miłosz-ML-015.jpg)

- Fragment of Heraclitus, marble & bronze, 1.2 m, Patmos, Greece (© Hirschfeld, 1994)

This article is taken from PN Review 257, Volume 47 Number 3, January - February 2021.