This item is taken from PN Review 285, Volume 52 Number 1, September - October 2025.

Pictures from a Library

Turning the Pages of the Manchester Guardian

August 1819 and a peaceful protest of some 60,000 men, women and children gather in St Peter’s Fields in Manchester to hear speeches against the inequalities of the British parliamentary system. Hacked down, as the orations begin, by soldiers on horseback brandishing sabres and trampled to ‘a mire of blood’ (P.B. Shelley), at least fifteen people die and 600 are injured. Known as the Peterloo Massacre, this event instantly becomes infamous and remains so to this day.

Appalled by the barbarity of Peterloo and the subsequent authoritarian crackdown, Manchester’s dissenting liberals decided to establish a newspaper to ‘warmly advocate the cause of parliamentary and social reform’ and seek for the demise of ‘antiquated and despotic governments’ (prospectus). This, after all, was a time when the still newfangled medium of a newspaper was capable of ‘enunciating communities and giving voice to city, country and region’ (Matthew Shaw), a far from negligible power in a town crammed with 100,000 inhabitants and not a single MP.

So from a cutler’s shop in Market Street one day in 1821 the Manchester Guardian rolled off the press for the first time at a price of 7d. Thriving, it quickly became the town’s best-selling paper and was soon punching above its weight on the national and international stage, ‘with a reputation for journalistic quality and integrity’ under the editorship of C.P. Scott.

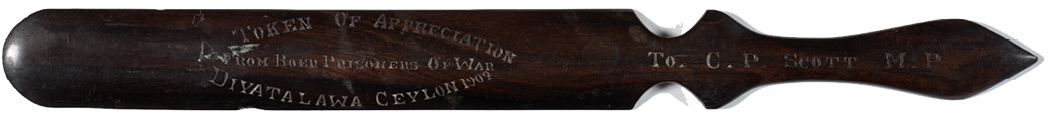

Radical and liberal in its values, Scott’s Manchester Guardian supported Irish Home Rule and women’s suffrage while condemning imperialism, facing hostile public opinion squarely when required. While his opposition to the Boer War lost his paper 15 percent of its circulation (Hannah Jenkinson), Scott persisted in his support for those detained who were dying of malnutrition and disease in internment camps, and all the while maintaining it was the best thing the paper did in his lifetime. A fact that was not lost on the otherwise forgotten prisoners of that self-same war still held in detention at Diyatalawa in Sri Lanka long after its end. The intangible comfort they drew from the solidarity expressed in a medium destined to be tomorrow’s chip wrappers, produced many thousands of miles away in a smoky, industrial town, took shape, exchanging signs for stuff (Steve Connor), to become an actual tangible object (shown here) as a token of their appreciation.

Deemed an essential piece of equipment and a most necessary accoutrement for the desk of a media mogul, the thing they made for Scott is called a page turner (defined here as an object as opposed to a practice). As J.J. Gibson observes, ‘things tell us what to do with them’, and here its ruler-like blade, carved in wood with rounded edges, suggests a purpose designed to assist in the process of turning pages without damage to paper or the transfer of ink to clean hands. And while it’s unlikely that Scott was squeamish on either account and had little need of its services, this still prized possession remains carefully preserved in his archive to confront us in the here and now.

Newspaper page turner presented to C.P. Scott, Editor of the Manchester Guardian, 1902.

Image provided by and © of The John Rylands Research Institute and Library, The University of Manchester

This item is taken from PN Review 285, Volume 52 Number 1, September - October 2025.