This article is taken from PN Review 284, Volume 51 Number 6, July - August 2025.

Pictures from a Library

Deeds, Words and Signs: a short history of the Broad Arrow

Stamped on goods, chattels and animals, the broad arrow, or King’s Mark, was first used to demarcate the property of the Crown during the Middle Ages. Originating from an actual weapon known as a pheon, this mace-like javelin was deployed in pageants and rituals to distinguish royalty. By the reign of Edward III it had also become a hieroglyphic of the nobility. As new technologies of war spread from China to the West guns and gunpowder were stockpiled to establish arsenals of ordnance. The broad arrow, branded onto every piece of military hardware and supplies, became the emblem of royal prerogative and possession, proclaiming ‘Noli me tangere, for Caeser’s I am’. To this day it remains a criminal offence to reproduce the broad arrow without authority.

Yet as every semiotician knows ‘each living sign has [at least] two faces’ (Valentin Voloshinov) and their meanings change and evolve through time and across contexts. So while heralds emblazoned azure-blue pheons onto the golden grounds of coats of arms, flaunting the rank, roots and affinities of the higher echelons of feudal power, others compelled to wear them deemed it a much less illustrious emblem and bore it with shame.

During the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries prisoners, for example, were forced to wear the broad arrow on their uniforms, denoting punishment and humiliation (Juliet Ash). Made of deliberately coarse material and uncomfortable to wear, the purpose of these garments was to stigmatise, deny individual identity and make inmates as tractable as any other piece of prison property. But signs ‘are created between individuals’ (Voloshinov) so some fought to resist the broad arrow’s power as the ‘visible embodiment of criminality’ (Ash) and as active agents tactically repurposed it for their own use.

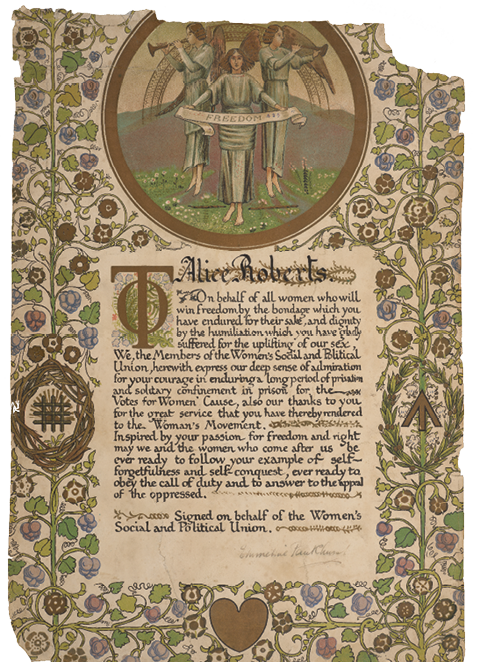

Between 1906 and 1914 some 1,300 people were arrested for their activism in support of women’s suffrage and most were sent to prison, including Sylvia Pankhurst. Subjected to solitary confinement, force feeding and the ignominy of the broad arrow, her experiences left her as strongly committed to prison reform as women’s emancipation. As a highly accomplished artist she, and her sister suffragettes, turned the tables on the authorities by reappropriating ‘the broad arrow motif and making it one of the most recognised symbols of the movement’ (Rachel Holmes). Rehabilitated for the cause, the broad arrow as a badge of honour was soon appearing everywhere on banners, bunting and regalia, ‘gilded and encased in a wreath of laurels signifying suffrage triumph’ (Richard Pankhurst). On suffrage demonstrations and processions, hundreds, glinting silver, were proudly carried aloft by those who had been imprisoned. Most poignant of all are those which Sylvia included on the illuminated certificates that were given to the imprisoned (as in the case shown here) as a potent symbol of each individual’s unique contribution to their cause and a resonant affirmation of their individuality. And though the suffragettes didn’t completely put paid to the broad arrow’s use in prisons, their contribution to its discrediting ensured its days were numbered.

Illuminated Certificate for Alice Roberts, signed by Emmeline Pankhurst and designed by Sylvia Pankhurst, 1906–10. © Estate of Sylvia Pankhurst; digital image provided by the John Rylands Research Institute and Library, University of Manchester.

This article is taken from PN Review 284, Volume 51 Number 6, July - August 2025.